Steeleye Span Part 1

Steeleye Span

Twenty-Seven Years on the Bus

by Steve Winick

Part 1

"Steeleye Span is like a bus," Maddy Prior explains. "It goes along, and people get on and get off it. Sometimes the bus goes along the route you want to go, and sometimes it turns off, so you get off." The only problem, she says, is that nobody's driving, and the bus tends to get lost.

After years of wandering, Steeleye Span have found their way, recovering a sense of identity that was largely lost in the 1980s. Their first studio album in seven years, Time, shows them to be much like the Steeleye Span of the mid-1970s, committed to combining traditional music with rock and roll in powerful and interesting ways. "The point we meet at is traditional music," says Prior, the band's long-time singer. "And rock...rock only in its application to what we do."

This firm resolve is particularly appropriate in light of the band's history. It was the first ensemble in Britain that was put together specifically to play "folk-rock" or, as some would rather say, "electric traditional music." The years have since brought other material into the band's repertoire, ranging from 1950s rock and roll to Berthold Brecht. But, at every concert since they were formed twenty-seven years ago, Steeleye Span has played traditional songs in a folk-rock style.

It is generally accepted that the style called "English folk-rock" was invented in 1969, when Fairport Convention recorded the seminal album Liege and Lief. Joe Boyd, who produced that album, once commented that it "opened the door through which a lot of good, mediocre and bad music rushed...." In the next twenty-seven years, Steeleye Span would push some of the first and best music through that door.

It is generally accepted that the style called "English folk-rock" was invented in 1969, when Fairport Convention recorded the seminal album Liege and Lief. Joe Boyd, who produced that album, once commented that it "opened the door through which a lot of good, mediocre and bad music rushed...." In the next twenty-seven years, Steeleye Span would push some of the first and best music through that door.

1969 was a momentous year for the members of Fairport Convention, filled with tragedies and triumphs that led directly to the founding of Steeleye Span. In May of that year, the band's van crashed, killing drummer Martin Lamble as well as guitarist Richard Thompson's girlfriend. After a period of recovery, the group held auditions for a new drummer and also added fiddler Dave Swarbrick to the band, which would later have consequences for Steeleye as well. By September they had released Liege and Lief, by far the group's most popular record at that time, and perhaps the most highly-regarded English folk album of all time. By November, Ashley Hutchings, the group's founder, decided to leave. And before the year turned, Hutchings had formed Steeleye Span. Although the conventional wisdom has always been that Hutchings left Fairport because of disagreements about the band's musical direction, in an interview with Sing Out! in 1996, Hutchings suggested that he had had a "minor breakdown." "My personal opinion is that it was a delayed reaction to the crash," he said.

Hutchings suggests that, if Fairport hadn't broken up when they did, there would have been no Steeleye Span. The same goes for the Irish folk pioneers Sweeney's Men, who were as important to the Irish folk revival as Fairport were to England's. In their brief time as a group, they introduced not only electricity but also the now-ubiquitous bouzouki to the Irish tradition. Originally a trio made up of Andy Irvine, Johnny Moynihan and Joe Dolan, they began to make waves in Dublin in 1966, combining the popular ballad-group aesthetic with gentler, subtler playing on bouzouki, mandolin, guitar and whistle. Soon Dolan had been replaced by Terry Woods, who added Appalachian banjo and other American influences to the group.

Hutchings suggests that, if Fairport hadn't broken up when they did, there would have been no Steeleye Span. The same goes for the Irish folk pioneers Sweeney's Men, who were as important to the Irish folk revival as Fairport were to England's. In their brief time as a group, they introduced not only electricity but also the now-ubiquitous bouzouki to the Irish tradition. Originally a trio made up of Andy Irvine, Johnny Moynihan and Joe Dolan, they began to make waves in Dublin in 1966, combining the popular ballad-group aesthetic with gentler, subtler playing on bouzouki, mandolin, guitar and whistle. Soon Dolan had been replaced by Terry Woods, who added Appalachian banjo and other American influences to the group.

Although all of Sweeney's Men's records are acoustic, there was a period in 1968 when electric guitarist Henry McCullough was part of the band. During this period they experimented with electric folk, becoming one of the few bands to have electrified Irish dance music before Fairport. Though McCullough left (to join Joe Cocker's band and play at Woodstock), the ideas were still fertile in the minds of Sweeney's two remaining members. When they moved to England, Hutchings quickly befriended them. A fan of their first album, which featured Irvine, Moynihan and Woods, Hutchings was originally interested in forming a band with that trio. However, Moynihan no longer relished working with Woods, and Irvine wouldn't join unless Moynihan came along, which left only Hutchings and Woods.

Hutchings and Woods were therefore looking for bandmates when Gay Woods, who had married Terry in 1968, came over to England to join her husband. "I got fed up in Ireland on my own," she explains. "I was a typist in Ireland, so I went to England to be a temp." She was an accomplished singer, but she had not performed professionally for several years, since, as she points out, "I had to earn the money!" Gay's arrival gave Hutchings the idea to form a band with the couple. "Terry Woods and I used to go up to Ashley's house and talk about the music, before it started to look like something real," Gay says. Still, they were sure they needed more people to flesh out the group. At one point, she claims, Robin and Barry Dransfield were going to be invited, but that band never came to fruition. Instead, Hutchings asked the folk duo of Tim Hart and Maddy Prior.

Hutchings and Woods were therefore looking for bandmates when Gay Woods, who had married Terry in 1968, came over to England to join her husband. "I got fed up in Ireland on my own," she explains. "I was a typist in Ireland, so I went to England to be a temp." She was an accomplished singer, but she had not performed professionally for several years, since, as she points out, "I had to earn the money!" Gay's arrival gave Hutchings the idea to form a band with the couple. "Terry Woods and I used to go up to Ashley's house and talk about the music, before it started to look like something real," Gay says. Still, they were sure they needed more people to flesh out the group. At one point, she claims, Robin and Barry Dransfield were going to be invited, but that band never came to fruition. Instead, Hutchings asked the folk duo of Tim Hart and Maddy Prior.

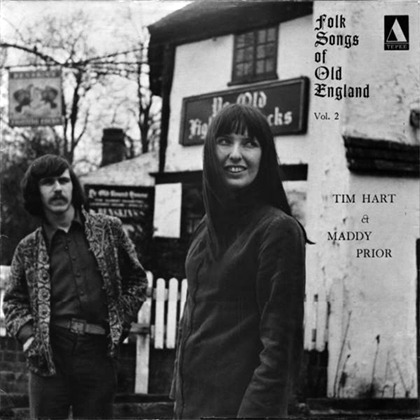

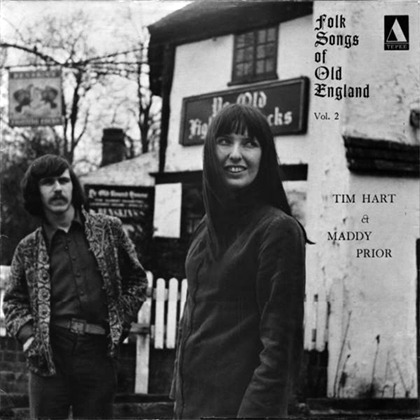

Prior and Hart were among Britain's best-known folk performers in the late 1960s. Like many of her generation, Prior got her start singing American songs. Ironically, it was two American friends who persuaded her to listen to English folksongs. They also introduced her to Ewan MacColl, a singer and activist who was a shaping force in the folk revival, and to Cecil Sharp House, England's major folksong archive. "They kind of put me on that trail," she says, "and I thought it was all rather odd until I got used to it." Hart had been in a rock band, the Ratfinks, before discovering folk music. The two met in their hometown of St. Alban's and began performing together in the late 60s. They were soon the toast of the folk club circuit, recording two highly regarded albums and touring all over England.

Prior and Hart were among Britain's best-known folk performers in the late 1960s. Like many of her generation, Prior got her start singing American songs. Ironically, it was two American friends who persuaded her to listen to English folksongs. They also introduced her to Ewan MacColl, a singer and activist who was a shaping force in the folk revival, and to Cecil Sharp House, England's major folksong archive. "They kind of put me on that trail," she says, "and I thought it was all rather odd until I got used to it." Hart had been in a rock band, the Ratfinks, before discovering folk music. The two met in their hometown of St. Alban's and began performing together in the late 60s. They were soon the toast of the folk club circuit, recording two highly regarded albums and touring all over England.

In 1969, Prior and Hart took part in a conversation at Keele folk festival about electrification of traditional music. Another participant in the discussion was Hutchings. As Hart told John Tobler in 1996, "We all sat around and expressed our annoyance that the electric input to folk music was coming from the rock side rather than the folk side...After that, Maddy and I gave Ashley a lift back to London and we got talking further." The result of these conversations was that, by the time he was sure of the Sweeneys' break-up, Hutchings knew whom he wanted in the band.

With Hart and Prior aboard, Steeleye Span began rehearsing.

Twenty-Seven Years on the Bus

by Steve Winick

Part 1

After years of wandering, Steeleye Span have found their way, recovering a sense of identity that was largely lost in the 1980s. Their first studio album in seven years, Time, shows them to be much like the Steeleye Span of the mid-1970s, committed to combining traditional music with rock and roll in powerful and interesting ways. "The point we meet at is traditional music," says Prior, the band's long-time singer. "And rock...rock only in its application to what we do."

This firm resolve is particularly appropriate in light of the band's history. It was the first ensemble in Britain that was put together specifically to play "folk-rock" or, as some would rather say, "electric traditional music." The years have since brought other material into the band's repertoire, ranging from 1950s rock and roll to Berthold Brecht. But, at every concert since they were formed twenty-seven years ago, Steeleye Span has played traditional songs in a folk-rock style.

It is generally accepted that the style called "English folk-rock" was invented in 1969, when Fairport Convention recorded the seminal album Liege and Lief. Joe Boyd, who produced that album, once commented that it "opened the door through which a lot of good, mediocre and bad music rushed...." In the next twenty-seven years, Steeleye Span would push some of the first and best music through that door.

It is generally accepted that the style called "English folk-rock" was invented in 1969, when Fairport Convention recorded the seminal album Liege and Lief. Joe Boyd, who produced that album, once commented that it "opened the door through which a lot of good, mediocre and bad music rushed...." In the next twenty-seven years, Steeleye Span would push some of the first and best music through that door.1969 was a momentous year for the members of Fairport Convention, filled with tragedies and triumphs that led directly to the founding of Steeleye Span. In May of that year, the band's van crashed, killing drummer Martin Lamble as well as guitarist Richard Thompson's girlfriend. After a period of recovery, the group held auditions for a new drummer and also added fiddler Dave Swarbrick to the band, which would later have consequences for Steeleye as well. By September they had released Liege and Lief, by far the group's most popular record at that time, and perhaps the most highly-regarded English folk album of all time. By November, Ashley Hutchings, the group's founder, decided to leave. And before the year turned, Hutchings had formed Steeleye Span. Although the conventional wisdom has always been that Hutchings left Fairport because of disagreements about the band's musical direction, in an interview with Sing Out! in 1996, Hutchings suggested that he had had a "minor breakdown." "My personal opinion is that it was a delayed reaction to the crash," he said.

Hutchings suggests that, if Fairport hadn't broken up when they did, there would have been no Steeleye Span. The same goes for the Irish folk pioneers Sweeney's Men, who were as important to the Irish folk revival as Fairport were to England's. In their brief time as a group, they introduced not only electricity but also the now-ubiquitous bouzouki to the Irish tradition. Originally a trio made up of Andy Irvine, Johnny Moynihan and Joe Dolan, they began to make waves in Dublin in 1966, combining the popular ballad-group aesthetic with gentler, subtler playing on bouzouki, mandolin, guitar and whistle. Soon Dolan had been replaced by Terry Woods, who added Appalachian banjo and other American influences to the group.

Hutchings suggests that, if Fairport hadn't broken up when they did, there would have been no Steeleye Span. The same goes for the Irish folk pioneers Sweeney's Men, who were as important to the Irish folk revival as Fairport were to England's. In their brief time as a group, they introduced not only electricity but also the now-ubiquitous bouzouki to the Irish tradition. Originally a trio made up of Andy Irvine, Johnny Moynihan and Joe Dolan, they began to make waves in Dublin in 1966, combining the popular ballad-group aesthetic with gentler, subtler playing on bouzouki, mandolin, guitar and whistle. Soon Dolan had been replaced by Terry Woods, who added Appalachian banjo and other American influences to the group.Although all of Sweeney's Men's records are acoustic, there was a period in 1968 when electric guitarist Henry McCullough was part of the band. During this period they experimented with electric folk, becoming one of the few bands to have electrified Irish dance music before Fairport. Though McCullough left (to join Joe Cocker's band and play at Woodstock), the ideas were still fertile in the minds of Sweeney's two remaining members. When they moved to England, Hutchings quickly befriended them. A fan of their first album, which featured Irvine, Moynihan and Woods, Hutchings was originally interested in forming a band with that trio. However, Moynihan no longer relished working with Woods, and Irvine wouldn't join unless Moynihan came along, which left only Hutchings and Woods.

Hutchings and Woods were therefore looking for bandmates when Gay Woods, who had married Terry in 1968, came over to England to join her husband. "I got fed up in Ireland on my own," she explains. "I was a typist in Ireland, so I went to England to be a temp." She was an accomplished singer, but she had not performed professionally for several years, since, as she points out, "I had to earn the money!" Gay's arrival gave Hutchings the idea to form a band with the couple. "Terry Woods and I used to go up to Ashley's house and talk about the music, before it started to look like something real," Gay says. Still, they were sure they needed more people to flesh out the group. At one point, she claims, Robin and Barry Dransfield were going to be invited, but that band never came to fruition. Instead, Hutchings asked the folk duo of Tim Hart and Maddy Prior.

Hutchings and Woods were therefore looking for bandmates when Gay Woods, who had married Terry in 1968, came over to England to join her husband. "I got fed up in Ireland on my own," she explains. "I was a typist in Ireland, so I went to England to be a temp." She was an accomplished singer, but she had not performed professionally for several years, since, as she points out, "I had to earn the money!" Gay's arrival gave Hutchings the idea to form a band with the couple. "Terry Woods and I used to go up to Ashley's house and talk about the music, before it started to look like something real," Gay says. Still, they were sure they needed more people to flesh out the group. At one point, she claims, Robin and Barry Dransfield were going to be invited, but that band never came to fruition. Instead, Hutchings asked the folk duo of Tim Hart and Maddy Prior. Prior and Hart were among Britain's best-known folk performers in the late 1960s. Like many of her generation, Prior got her start singing American songs. Ironically, it was two American friends who persuaded her to listen to English folksongs. They also introduced her to Ewan MacColl, a singer and activist who was a shaping force in the folk revival, and to Cecil Sharp House, England's major folksong archive. "They kind of put me on that trail," she says, "and I thought it was all rather odd until I got used to it." Hart had been in a rock band, the Ratfinks, before discovering folk music. The two met in their hometown of St. Alban's and began performing together in the late 60s. They were soon the toast of the folk club circuit, recording two highly regarded albums and touring all over England.

Prior and Hart were among Britain's best-known folk performers in the late 1960s. Like many of her generation, Prior got her start singing American songs. Ironically, it was two American friends who persuaded her to listen to English folksongs. They also introduced her to Ewan MacColl, a singer and activist who was a shaping force in the folk revival, and to Cecil Sharp House, England's major folksong archive. "They kind of put me on that trail," she says, "and I thought it was all rather odd until I got used to it." Hart had been in a rock band, the Ratfinks, before discovering folk music. The two met in their hometown of St. Alban's and began performing together in the late 60s. They were soon the toast of the folk club circuit, recording two highly regarded albums and touring all over England.In 1969, Prior and Hart took part in a conversation at Keele folk festival about electrification of traditional music. Another participant in the discussion was Hutchings. As Hart told John Tobler in 1996, "We all sat around and expressed our annoyance that the electric input to folk music was coming from the rock side rather than the folk side...After that, Maddy and I gave Ashley a lift back to London and we got talking further." The result of these conversations was that, by the time he was sure of the Sweeneys' break-up, Hutchings knew whom he wanted in the band.

With Hart and Prior aboard, Steeleye Span began rehearsing.