Steeleye Span Part 2

Steeleye Span

Twenty-Seven Years on the Bus

by Steve Winick

Part 2

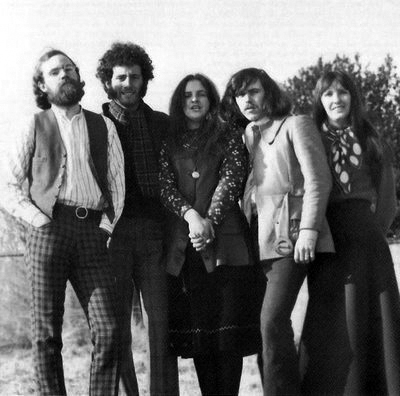

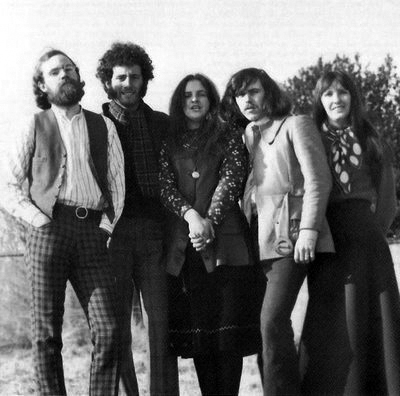

The quintet of Maddy Prior, Tim Hart, Gay and Terry Woods and Ashley Hutchings, the first lineup of Steeleye Span, was an inherently unstable configuration, which Prior today refers to as "two couples and a referee."

Hart elaborates: "Maddy and I were a clearly defined unit with our own ideas, Ashley had his ideas...and Terry and Gay had their ideas which tended to pull in a different direction."

In trying to describe the difficulty this band had in coming to a consensus, the great English folksinger and guitarist Martin Carthy tells the story of how Steeleye Span got its name. In late 1969, Carthy recounts, Hart approached him for ideas about what to call the new group. "I'd just learned this particular song, called 'Horkstow Grange.' One of the characters in it was called John Span, and his nickname was Steeleye. I said, 'Isn't that a great name, Steeleye Span.' And Tim said, 'Sounds like a name for a band to me!' He wrote it down." What happened next was typical of this lineup: "Everybody had different names that they wanted to call the band, so they decided to put it to the vote. Tim voted twice, so the band was called Steeleye Span!"

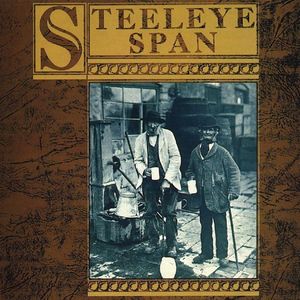

After a few months of rehearsals at a country house in Wiltshire, the first step the new band took was to record an album, Hark! The Village Wait (1970). Asked why they leapt straight into the recording studio, Prior shrugs: "The record company had given us the money!" The world can count itself lucky, for had they gone out on tour, the band might well have broken up without ever recording a note. That would have been unfortunate; although a bit tentative, Hark! The Village Wait is clearly a worthy addition to the folk-rock canon, and presents a richly varied array of songs from Britain and Ireland that is enjoyable listening even today. Strong vocals from four singers, and instruments as diverse as concertina, autoharp, electric dulcimer, mandola, banjo and harmonium in addition to electric guitar, bass and drums made the original Steeleye much more versatile than their fellow folk-rockers Fairport Convention. Prior agrees with this assessment of their first attempt: "I've always liked it as an album...it has a sort of freshness about it," she says.

After a few months of rehearsals at a country house in Wiltshire, the first step the new band took was to record an album, Hark! The Village Wait (1970). Asked why they leapt straight into the recording studio, Prior shrugs: "The record company had given us the money!" The world can count itself lucky, for had they gone out on tour, the band might well have broken up without ever recording a note. That would have been unfortunate; although a bit tentative, Hark! The Village Wait is clearly a worthy addition to the folk-rock canon, and presents a richly varied array of songs from Britain and Ireland that is enjoyable listening even today. Strong vocals from four singers, and instruments as diverse as concertina, autoharp, electric dulcimer, mandola, banjo and harmonium in addition to electric guitar, bass and drums made the original Steeleye much more versatile than their fellow folk-rockers Fairport Convention. Prior agrees with this assessment of their first attempt: "I've always liked it as an album...it has a sort of freshness about it," she says.

Despite their success in making an album that came close to their ideal of "electric traditional music," and despite the generally positive response from listeners, the original Steeleye Span never survived to play a single concert; in fact, they decided to break up before the album was even finished. Musical disagreements were secondary to personal clashes, according to all concerned. Prior remembers it as a time of "stresses and strains and difficulties and arguments and throwing beer over each other's heads."

Gay Woods attributes part of the problem to the group's living arrangements. "We didn't understand what being a group was about, you know, leaving space for each individual to develop. We even had the cheek to try and live together!"

Gay Woods attributes part of the problem to the group's living arrangements. "We didn't understand what being a group was about, you know, leaving space for each individual to develop. We even had the cheek to try and live together!"

Prior agrees that living together was a mistake. "Our friend had a house, so we just said, 'Oh, that would be great!' Which in theory it would have been..." she trails off, laughing.

After the breakup, the Woodses left to be part of a band called Dr. Strangely Strange, and then to form the Woods Band. Prior, Hart and Hutchings decided to push on with Steeleye Span, and set their sights on Martin Carthy. A more established figure within the folk club scene than Prior and Hart, Carthy would lend Steeleye Span some credibility among the folk audience. The fact that Carthy's touring partner, Dave Swarbrick, had gone off to be in Fairport Convention, and the fact that his marriage broke up that same year, made him a free agent and game for anything...once they managed to track him down. "My wife and I had just split up, so I didn't have anywhere to live," he explains." From about the middle of January until about the middle of May, I went on this tour."

Finally, Steeleye found him. "I went visiting my daughter one time, and the phone rang. It was Tim, and he said, 'How'd you like to join Steeleye Span?' And I said, 'Yeah, all right.'" After travelling to London to meet up with the remaining three Steeleye members, Carthy went out and bought an electric guitar. "I didn't think about it, I just did it. I didn't actually treat it as an electric guitar. I just put a set of medium-gauge strings on this Telecaster and played it the way I'd always played. So it was just more or less what I did before only louder. I loved it! Ooh!"

This lineup set out to be musical ambassadors for traditional song and music, hoping to bring it to new audiences in an accessible way. Before touring or recording, however, they decided that they needed another element to their sound. Carthy, who was freshest off the folk club scene, was their talent scout, recommending a young violinist named Peter Knight. At the time, Knight was playing as a duo with singer/guitarist Bob Johnson, but he had had a long and varied musical history before that.

After an auspicious start (four years at the Royal Academy of Music, starting at the age of 13) Knight took a few years off in his later teens to discover the mysteries of the opposite sex. But then his life was changed by his first exposure to folk music. "I heard an Irish recording by an Irish fiddle player called Michael Coleman, and absolutely loved it." Soon, he was sitting in at pubs where Irish music was played, and ultimately hooked up with Johnson to play the club scene. As Knight tells it, Carthy was rather conspicuously watching the duo at quite a few of their gigs. "We were saying 'Oh, God, there's Martin Carthy again!'" Soon after that, he got a phone call from Hutchings and joined the band.

After an auspicious start (four years at the Royal Academy of Music, starting at the age of 13) Knight took a few years off in his later teens to discover the mysteries of the opposite sex. But then his life was changed by his first exposure to folk music. "I heard an Irish recording by an Irish fiddle player called Michael Coleman, and absolutely loved it." Soon, he was sitting in at pubs where Irish music was played, and ultimately hooked up with Johnson to play the club scene. As Knight tells it, Carthy was rather conspicuously watching the duo at quite a few of their gigs. "We were saying 'Oh, God, there's Martin Carthy again!'" Soon after that, he got a phone call from Hutchings and joined the band.

The second Steeleye lineup was soon on the road, playing the college circuit to crowds of several hundred people. As lineups go, this one seems to be famed for the sheer volume of its playing. "We all played bloody loud!" Carthy remembers. "It was a loud band, and if anybody suggested that we turn down, I'd tell them to get stuffed, because it was a great sound. We were using big amps, for God's sake. We were using the Fender dual Showman. It's a five foot high speaker! So in order to get any kind of sound, you've got to turn up to a volume."

Prior agrees: "People used to say, "I can't hear the words.' We had 400 watts of PA! And you think anybody else plays loud, you should be in front of Martin Carthy! People fondly imagine Martin being very restrained...not a bit of it! There wouldn't be any chance of hearing the words. I never heard them, that's for sure!"

Even so, Carthy remembers hearing very few negative reactions from folk fans, which went directly against their expectations. "What sometimes we forget," he says, "is that the folkies used to come and see Steeleye! They love 'em! We never really ran into any flak from these mythical purists. Of course there were some people who didn't like it, but we have to admit that the people we thought might be pissed off weren't pissed off. The only time we ever got trouble was from rock and roll purists. One guy actually went on the stage and tried to pull Peter's fiddle out of his hand, 'cause it wasn't rock and roll!"

This incarnation of Steeleye Span recorded two very different albums. Please to See the King (1971) incorporated Carthy's droning guitar style, and edged Knight's fiddle with distortion. The results were mixed, sometimes muddy but always interesting. The whimsically named Ten Man Mop, or: Mr. Reservoir-Butler Rides Again (1971) is Steeleye's most acoustic-sounding album, and also contains the most Irish material. The vocals are more to the fore, the fiddling is fluid, and the band sounds more comfortable with its new members.

This incarnation of Steeleye Span recorded two very different albums. Please to See the King (1971) incorporated Carthy's droning guitar style, and edged Knight's fiddle with distortion. The results were mixed, sometimes muddy but always interesting. The whimsically named Ten Man Mop, or: Mr. Reservoir-Butler Rides Again (1971) is Steeleye's most acoustic-sounding album, and also contains the most Irish material. The vocals are more to the fore, the fiddling is fluid, and the band sounds more comfortable with its new members.

Indeed, Carthy suggests that the band had become altogether too comfortable. "We'd come to an end," he laments. "We'd stopped thinking." Hutchings was one person who never stopped thinking, and he could see that Steeleye was not going in the direction he wanted to go. A long stint during which Steeleye played for a theatre company, and the increasingly Irish repertoire the band was playing, encouraged the naturally restless Hutchings to move on to his next project: an electric band that played purely English folk music, known as The Albion Band.

After a brief period of negotiation, Carthy left as well. After Hutchings left, he explains, most of the band wanted to bring in another bass player and continue in the same vein. Carthy wanted another challenge, and suggested asking John Kirkpatrick, a singer, dancer and melodeon and concertina player, to join. "I was the only one who was interested in that," he remembers. "The others just wanted to get going. And since I was the only one who was that interested in this other idea, something had to give, and I was really sad when I realized I was gonna have to leave. Since I was the one who felt strongly about it, I was the one who had to go...but it was a really hard decision to make."

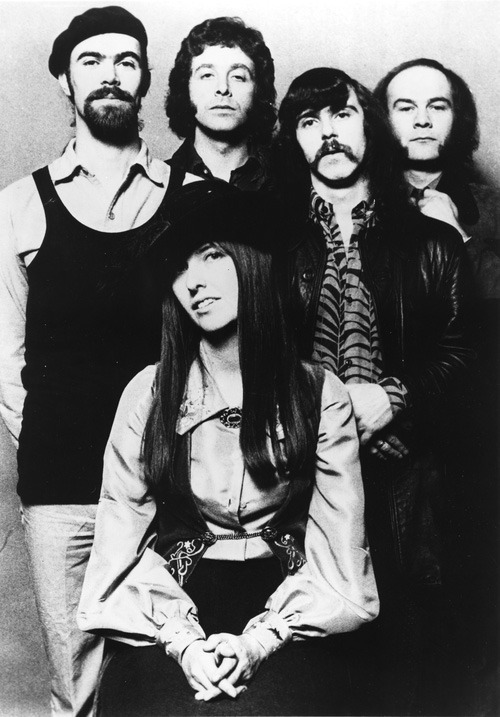

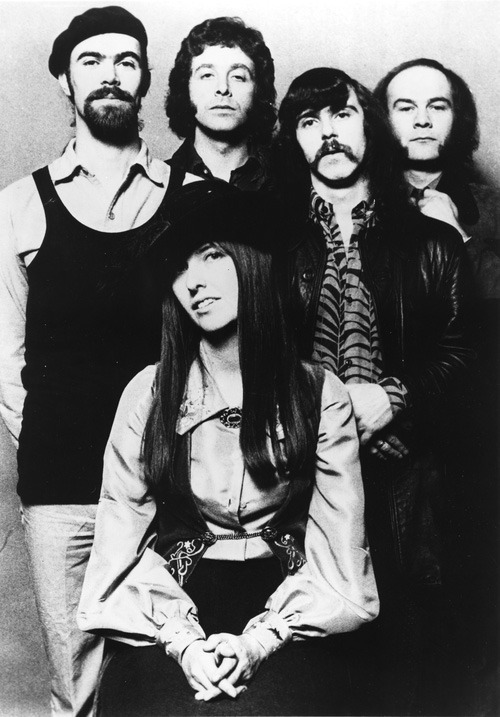

The bass player chosen to replace Hutchings was Rick Kemp, an extremely solid player who had worked a lot with Mike Chapman and had had a brief stint with King Crimson. Unlike the other members of Steeleye, he hadn't had any experience with folk music at all, so he brought more of a straight rock and roll vibe to the band. In this he would be supported by Robert Johnson, Knight's former musical partner, who joined the group on guitar.

Johnson, whose guitar playing was influenced by his Mississippi namesake, was the logical choice for Steeleye in several ways. For one, as Carthy points out, "we'd actually sort of robbed Bob of his partner when we asked Peter to join the band." Also, despite his own claim that "Peter got me into the band 'cause I was his friend...nobody else had heard of me at all," Johnson was remembered by true folk aficionados as a fine guitar player. Although Johnson had given up professional music and was working as a computer programmer, Carthy still recalled seeing him in the clubs and being mightily impressed by his "dense, very clever arrangements" and his "very, very classy" guitar playing.

Johnson, whose guitar playing was influenced by his Mississippi namesake, was the logical choice for Steeleye in several ways. For one, as Carthy points out, "we'd actually sort of robbed Bob of his partner when we asked Peter to join the band." Also, despite his own claim that "Peter got me into the band 'cause I was his friend...nobody else had heard of me at all," Johnson was remembered by true folk aficionados as a fine guitar player. Although Johnson had given up professional music and was working as a computer programmer, Carthy still recalled seeing him in the clubs and being mightily impressed by his "dense, very clever arrangements" and his "very, very classy" guitar playing.

The chief reason that Johnson was a perfect match for Steeleye, however, was something of which the band was completely unaware: for years, he had been just itching to blend traditional music and rock and roll. "The idea was always for me that the electric guitar, and the rockier, harder more simple sounds of rock and roll were quite suited to the harsh, hard stories behind a lot of those ballads and songs," he says. "It had been in the back of my mind before joining Steeleye Span, actually, on several occasions. I wondered what it would be like to play folk music but in a rocky way, an electric way. But it was not something I could ever suggest or think about in the bands that I was in. So it was very much a fluke that I was actually asked to join the band that was already starting to do the sort of thing that I did once think about myself. Not very often in life that things happen like that."

Johnson's progression as both a fan and a musician had been from rock to folk. Starting with early rock and rollers like Chuck Berry and Carl Perkins, he "went backwards," as he puts it, to bluesmen Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf and early country stars George Jones, Buck Owens and Hank Williams. From there, he began to explore American folk music in the early folk clubs, and from there "went backwards" still further to British and Irish folk songs. Carthy was a big influence on Johnson in the folk stage, "...only because of the way he seemed to get inside the song, inside the story of the song," he explains, hastening to add, "I didn't try to sing like him or play like him."

Like Carthy, Johnson had always been captivated by the stories of the ballads, especially supernatural ballads about witches, ghosts and elves. "Even when I was little," he elaborates, "I was an escapist sort of person, and I read fairy stories. In English Literature classes we would read the ballads. I remember reading 'Thomas the Rhymer' then, at school." "Thomas the Rhymer" and other supernatural ballads, dressed up in Johnson's elaborate arrangements, became the backbone of Steeleye's repertoire, so much so that Carthy believes it is Johnson's personality, more than anyone else's, that has defined Steeleye Span.

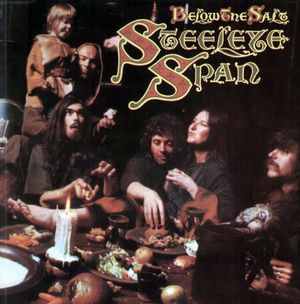

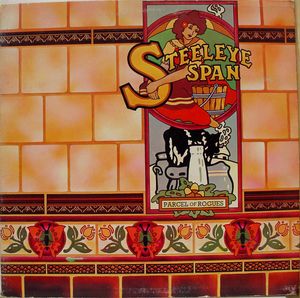

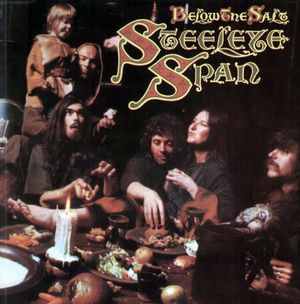

Johnson, Kemp, Prior, Hart and Knight made a formidable band, and Steeleye's next two albums, Below the Salt (1972) and Parcel of Rogues (1973), are considered classics of the genre. For some staunch Steeleye fans, these two records have never been surpassed. Prior sees this as a transitional period, before drums re-entered the group's sound (only Hark! The Village Wait had featured drums), but after Kemp's percussive bass and Johnson's hard-edged rock guitar began exerting their influence. "Those two albums were very distinctive, very different from what had gone before and what came afterwards," she says. "I think Bob and Rick having an essentially pure rock n roll [background], gave it a different slant completely from what had gone before. It's a different balance and crossover. We were starting to move towards a more accessible rock format, rock and roll as it were."

Johnson, Kemp, Prior, Hart and Knight made a formidable band, and Steeleye's next two albums, Below the Salt (1972) and Parcel of Rogues (1973), are considered classics of the genre. For some staunch Steeleye fans, these two records have never been surpassed. Prior sees this as a transitional period, before drums re-entered the group's sound (only Hark! The Village Wait had featured drums), but after Kemp's percussive bass and Johnson's hard-edged rock guitar began exerting their influence. "Those two albums were very distinctive, very different from what had gone before and what came afterwards," she says. "I think Bob and Rick having an essentially pure rock n roll [background], gave it a different slant completely from what had gone before. It's a different balance and crossover. We were starting to move towards a more accessible rock format, rock and roll as it were."

In addition to this toughening up of Steeleye's sound, their material on those two albums was stronger than ever. Johnson's arrangement of the ballad "King Henry" from Below the Salt was in his words "my first deliberate, conscious attempt to go into the ballad collections, find one and try and arrange it in some way and make it rocky." It is a long song that tells a strong, simple story, broken up into several parts by changes in rhythm, all handled beautifully by the band and particularly by Johnson and Kemp. Other classics from Below the Salt include the pastoral ditties "Rosebud in June" and "Spotted Cow" and the group's rendition of "John Barleycorn," one of the best-loved of Britain's traditional songs.

Despite the strength of the "folk" material, Below the Salt's runaway hit was "Gaudete," a Latin chant celebrating the birth of Christ, sung a capella in five-part harmony. The single was Steeleye's first big hit, reaching number fourteen in the British charts. "We were on Top of the Pops with it," Prior exclaims. "It was extraordinary! As it was then, which was kind of like all tits and bums and stuff, to go on to sing this Latin chant was extraordinary!" Not everyone loved it, however. "When we recorded it, the engineer loathed it. Absolutely hated it. So that's why it's got a very long fade in and a very long fade out," Prior explains.

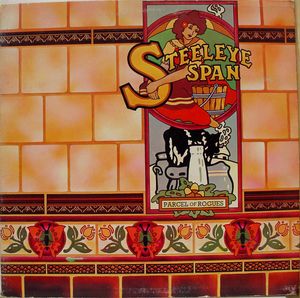

The success of "Gaudete" helped push Below the Salt to number 43 on the album charts, but it was Parcel of Rogues that first took them into the top 30. Even more searingly electric than Below the Salt, it includes some moments that verge on heavy metal. Still, the strong vocal harmonies and the focus on traditional material, particularly several Jacobite songs, made it a hit with some folkies as well. Songs like "Alison Gross" and "The Wee, Wee Man" continued to demonstrate Johnson's love of the supernatural, while "Hares on the Mountain" and "One Misty Moisty Morning" were successors to Below the Salt's more pastoral pieces.

Despite the strength of the "folk" material, Below the Salt's runaway hit was "Gaudete," a Latin chant celebrating the birth of Christ, sung a capella in five-part harmony. The single was Steeleye's first big hit, reaching number fourteen in the British charts. "We were on Top of the Pops with it," Prior exclaims. "It was extraordinary! As it was then, which was kind of like all tits and bums and stuff, to go on to sing this Latin chant was extraordinary!" Not everyone loved it, however. "When we recorded it, the engineer loathed it. Absolutely hated it. So that's why it's got a very long fade in and a very long fade out," Prior explains.

The success of "Gaudete" helped push Below the Salt to number 43 on the album charts, but it was Parcel of Rogues that first took them into the top 30. Even more searingly electric than Below the Salt, it includes some moments that verge on heavy metal. Still, the strong vocal harmonies and the focus on traditional material, particularly several Jacobite songs, made it a hit with some folkies as well. Songs like "Alison Gross" and "The Wee, Wee Man" continued to demonstrate Johnson's love of the supernatural, while "Hares on the Mountain" and "One Misty Moisty Morning" were successors to Below the Salt's more pastoral pieces.

Also on Parcel Of Rogues, Prior showed her commitment to more worldly concerns in her arrangement of "The Weaver and the Factory Maid," which, she says, "is a song about change, you see. How different generations respond to change. In 'Weaver,' the young man thinks [the factory] is quite good 'cause there's all these girls, and the old man thinks it's terrible because the whole trade is going downhill. And those are not attitudes that have changed." In fact, the older generation's rejection of new technologies while youngsters enjoy their liberating qualities was a feature of the electric folk movement in Britain, out of which Steeleye Span arose, making the song a sort of analogy for Steeleye itself.

Also on Parcel Of Rogues, Prior showed her commitment to more worldly concerns in her arrangement of "The Weaver and the Factory Maid," which, she says, "is a song about change, you see. How different generations respond to change. In 'Weaver,' the young man thinks [the factory] is quite good 'cause there's all these girls, and the old man thinks it's terrible because the whole trade is going downhill. And those are not attitudes that have changed." In fact, the older generation's rejection of new technologies while youngsters enjoy their liberating qualities was a feature of the electric folk movement in Britain, out of which Steeleye Span arose, making the song a sort of analogy for Steeleye itself.

A single song on Parcel Of Rogues featured a guest drummer. Soon, at the urging of Rick Kemp, the band began looking for a full-time drummer to fulfill its rock and roll destiny. They came up with Nigel Pegrum. "It took us a while to find Nigel," Prior remembers, "because we wanted someone who was quite musical. He played flute as well. He came in on that level as well, so we didn't have to have drums all the time, although it worked out that that's mostly what he did."

With Pegrum in tow, Steeleye Span became the "classic" lineup that would reach dizzying heights of popularity and sobering depths of disarray, a lineup that would disband, regroup, and fragment again.

But Steeleye would survive.

Twenty-Seven Years on the Bus

by Steve Winick

Part 2

The quintet of Maddy Prior, Tim Hart, Gay and Terry Woods and Ashley Hutchings, the first lineup of Steeleye Span, was an inherently unstable configuration, which Prior today refers to as "two couples and a referee."

Hart elaborates: "Maddy and I were a clearly defined unit with our own ideas, Ashley had his ideas...and Terry and Gay had their ideas which tended to pull in a different direction."

In trying to describe the difficulty this band had in coming to a consensus, the great English folksinger and guitarist Martin Carthy tells the story of how Steeleye Span got its name. In late 1969, Carthy recounts, Hart approached him for ideas about what to call the new group. "I'd just learned this particular song, called 'Horkstow Grange.' One of the characters in it was called John Span, and his nickname was Steeleye. I said, 'Isn't that a great name, Steeleye Span.' And Tim said, 'Sounds like a name for a band to me!' He wrote it down." What happened next was typical of this lineup: "Everybody had different names that they wanted to call the band, so they decided to put it to the vote. Tim voted twice, so the band was called Steeleye Span!"

After a few months of rehearsals at a country house in Wiltshire, the first step the new band took was to record an album, Hark! The Village Wait (1970). Asked why they leapt straight into the recording studio, Prior shrugs: "The record company had given us the money!" The world can count itself lucky, for had they gone out on tour, the band might well have broken up without ever recording a note. That would have been unfortunate; although a bit tentative, Hark! The Village Wait is clearly a worthy addition to the folk-rock canon, and presents a richly varied array of songs from Britain and Ireland that is enjoyable listening even today. Strong vocals from four singers, and instruments as diverse as concertina, autoharp, electric dulcimer, mandola, banjo and harmonium in addition to electric guitar, bass and drums made the original Steeleye much more versatile than their fellow folk-rockers Fairport Convention. Prior agrees with this assessment of their first attempt: "I've always liked it as an album...it has a sort of freshness about it," she says.

After a few months of rehearsals at a country house in Wiltshire, the first step the new band took was to record an album, Hark! The Village Wait (1970). Asked why they leapt straight into the recording studio, Prior shrugs: "The record company had given us the money!" The world can count itself lucky, for had they gone out on tour, the band might well have broken up without ever recording a note. That would have been unfortunate; although a bit tentative, Hark! The Village Wait is clearly a worthy addition to the folk-rock canon, and presents a richly varied array of songs from Britain and Ireland that is enjoyable listening even today. Strong vocals from four singers, and instruments as diverse as concertina, autoharp, electric dulcimer, mandola, banjo and harmonium in addition to electric guitar, bass and drums made the original Steeleye much more versatile than their fellow folk-rockers Fairport Convention. Prior agrees with this assessment of their first attempt: "I've always liked it as an album...it has a sort of freshness about it," she says.Despite their success in making an album that came close to their ideal of "electric traditional music," and despite the generally positive response from listeners, the original Steeleye Span never survived to play a single concert; in fact, they decided to break up before the album was even finished. Musical disagreements were secondary to personal clashes, according to all concerned. Prior remembers it as a time of "stresses and strains and difficulties and arguments and throwing beer over each other's heads."

Gay Woods attributes part of the problem to the group's living arrangements. "We didn't understand what being a group was about, you know, leaving space for each individual to develop. We even had the cheek to try and live together!"

Gay Woods attributes part of the problem to the group's living arrangements. "We didn't understand what being a group was about, you know, leaving space for each individual to develop. We even had the cheek to try and live together!"Prior agrees that living together was a mistake. "Our friend had a house, so we just said, 'Oh, that would be great!' Which in theory it would have been..." she trails off, laughing.

After the breakup, the Woodses left to be part of a band called Dr. Strangely Strange, and then to form the Woods Band. Prior, Hart and Hutchings decided to push on with Steeleye Span, and set their sights on Martin Carthy. A more established figure within the folk club scene than Prior and Hart, Carthy would lend Steeleye Span some credibility among the folk audience. The fact that Carthy's touring partner, Dave Swarbrick, had gone off to be in Fairport Convention, and the fact that his marriage broke up that same year, made him a free agent and game for anything...once they managed to track him down. "My wife and I had just split up, so I didn't have anywhere to live," he explains." From about the middle of January until about the middle of May, I went on this tour."

Finally, Steeleye found him. "I went visiting my daughter one time, and the phone rang. It was Tim, and he said, 'How'd you like to join Steeleye Span?' And I said, 'Yeah, all right.'" After travelling to London to meet up with the remaining three Steeleye members, Carthy went out and bought an electric guitar. "I didn't think about it, I just did it. I didn't actually treat it as an electric guitar. I just put a set of medium-gauge strings on this Telecaster and played it the way I'd always played. So it was just more or less what I did before only louder. I loved it! Ooh!"

This lineup set out to be musical ambassadors for traditional song and music, hoping to bring it to new audiences in an accessible way. Before touring or recording, however, they decided that they needed another element to their sound. Carthy, who was freshest off the folk club scene, was their talent scout, recommending a young violinist named Peter Knight. At the time, Knight was playing as a duo with singer/guitarist Bob Johnson, but he had had a long and varied musical history before that.

After an auspicious start (four years at the Royal Academy of Music, starting at the age of 13) Knight took a few years off in his later teens to discover the mysteries of the opposite sex. But then his life was changed by his first exposure to folk music. "I heard an Irish recording by an Irish fiddle player called Michael Coleman, and absolutely loved it." Soon, he was sitting in at pubs where Irish music was played, and ultimately hooked up with Johnson to play the club scene. As Knight tells it, Carthy was rather conspicuously watching the duo at quite a few of their gigs. "We were saying 'Oh, God, there's Martin Carthy again!'" Soon after that, he got a phone call from Hutchings and joined the band.

After an auspicious start (four years at the Royal Academy of Music, starting at the age of 13) Knight took a few years off in his later teens to discover the mysteries of the opposite sex. But then his life was changed by his first exposure to folk music. "I heard an Irish recording by an Irish fiddle player called Michael Coleman, and absolutely loved it." Soon, he was sitting in at pubs where Irish music was played, and ultimately hooked up with Johnson to play the club scene. As Knight tells it, Carthy was rather conspicuously watching the duo at quite a few of their gigs. "We were saying 'Oh, God, there's Martin Carthy again!'" Soon after that, he got a phone call from Hutchings and joined the band.The second Steeleye lineup was soon on the road, playing the college circuit to crowds of several hundred people. As lineups go, this one seems to be famed for the sheer volume of its playing. "We all played bloody loud!" Carthy remembers. "It was a loud band, and if anybody suggested that we turn down, I'd tell them to get stuffed, because it was a great sound. We were using big amps, for God's sake. We were using the Fender dual Showman. It's a five foot high speaker! So in order to get any kind of sound, you've got to turn up to a volume."

Prior agrees: "People used to say, "I can't hear the words.' We had 400 watts of PA! And you think anybody else plays loud, you should be in front of Martin Carthy! People fondly imagine Martin being very restrained...not a bit of it! There wouldn't be any chance of hearing the words. I never heard them, that's for sure!"

Even so, Carthy remembers hearing very few negative reactions from folk fans, which went directly against their expectations. "What sometimes we forget," he says, "is that the folkies used to come and see Steeleye! They love 'em! We never really ran into any flak from these mythical purists. Of course there were some people who didn't like it, but we have to admit that the people we thought might be pissed off weren't pissed off. The only time we ever got trouble was from rock and roll purists. One guy actually went on the stage and tried to pull Peter's fiddle out of his hand, 'cause it wasn't rock and roll!"

This incarnation of Steeleye Span recorded two very different albums. Please to See the King (1971) incorporated Carthy's droning guitar style, and edged Knight's fiddle with distortion. The results were mixed, sometimes muddy but always interesting. The whimsically named Ten Man Mop, or: Mr. Reservoir-Butler Rides Again (1971) is Steeleye's most acoustic-sounding album, and also contains the most Irish material. The vocals are more to the fore, the fiddling is fluid, and the band sounds more comfortable with its new members.

This incarnation of Steeleye Span recorded two very different albums. Please to See the King (1971) incorporated Carthy's droning guitar style, and edged Knight's fiddle with distortion. The results were mixed, sometimes muddy but always interesting. The whimsically named Ten Man Mop, or: Mr. Reservoir-Butler Rides Again (1971) is Steeleye's most acoustic-sounding album, and also contains the most Irish material. The vocals are more to the fore, the fiddling is fluid, and the band sounds more comfortable with its new members.Indeed, Carthy suggests that the band had become altogether too comfortable. "We'd come to an end," he laments. "We'd stopped thinking." Hutchings was one person who never stopped thinking, and he could see that Steeleye was not going in the direction he wanted to go. A long stint during which Steeleye played for a theatre company, and the increasingly Irish repertoire the band was playing, encouraged the naturally restless Hutchings to move on to his next project: an electric band that played purely English folk music, known as The Albion Band.

After a brief period of negotiation, Carthy left as well. After Hutchings left, he explains, most of the band wanted to bring in another bass player and continue in the same vein. Carthy wanted another challenge, and suggested asking John Kirkpatrick, a singer, dancer and melodeon and concertina player, to join. "I was the only one who was interested in that," he remembers. "The others just wanted to get going. And since I was the only one who was that interested in this other idea, something had to give, and I was really sad when I realized I was gonna have to leave. Since I was the one who felt strongly about it, I was the one who had to go...but it was a really hard decision to make."

The bass player chosen to replace Hutchings was Rick Kemp, an extremely solid player who had worked a lot with Mike Chapman and had had a brief stint with King Crimson. Unlike the other members of Steeleye, he hadn't had any experience with folk music at all, so he brought more of a straight rock and roll vibe to the band. In this he would be supported by Robert Johnson, Knight's former musical partner, who joined the group on guitar.

Johnson, whose guitar playing was influenced by his Mississippi namesake, was the logical choice for Steeleye in several ways. For one, as Carthy points out, "we'd actually sort of robbed Bob of his partner when we asked Peter to join the band." Also, despite his own claim that "Peter got me into the band 'cause I was his friend...nobody else had heard of me at all," Johnson was remembered by true folk aficionados as a fine guitar player. Although Johnson had given up professional music and was working as a computer programmer, Carthy still recalled seeing him in the clubs and being mightily impressed by his "dense, very clever arrangements" and his "very, very classy" guitar playing.

Johnson, whose guitar playing was influenced by his Mississippi namesake, was the logical choice for Steeleye in several ways. For one, as Carthy points out, "we'd actually sort of robbed Bob of his partner when we asked Peter to join the band." Also, despite his own claim that "Peter got me into the band 'cause I was his friend...nobody else had heard of me at all," Johnson was remembered by true folk aficionados as a fine guitar player. Although Johnson had given up professional music and was working as a computer programmer, Carthy still recalled seeing him in the clubs and being mightily impressed by his "dense, very clever arrangements" and his "very, very classy" guitar playing.The chief reason that Johnson was a perfect match for Steeleye, however, was something of which the band was completely unaware: for years, he had been just itching to blend traditional music and rock and roll. "The idea was always for me that the electric guitar, and the rockier, harder more simple sounds of rock and roll were quite suited to the harsh, hard stories behind a lot of those ballads and songs," he says. "It had been in the back of my mind before joining Steeleye Span, actually, on several occasions. I wondered what it would be like to play folk music but in a rocky way, an electric way. But it was not something I could ever suggest or think about in the bands that I was in. So it was very much a fluke that I was actually asked to join the band that was already starting to do the sort of thing that I did once think about myself. Not very often in life that things happen like that."

Johnson's progression as both a fan and a musician had been from rock to folk. Starting with early rock and rollers like Chuck Berry and Carl Perkins, he "went backwards," as he puts it, to bluesmen Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf and early country stars George Jones, Buck Owens and Hank Williams. From there, he began to explore American folk music in the early folk clubs, and from there "went backwards" still further to British and Irish folk songs. Carthy was a big influence on Johnson in the folk stage, "...only because of the way he seemed to get inside the song, inside the story of the song," he explains, hastening to add, "I didn't try to sing like him or play like him."

Like Carthy, Johnson had always been captivated by the stories of the ballads, especially supernatural ballads about witches, ghosts and elves. "Even when I was little," he elaborates, "I was an escapist sort of person, and I read fairy stories. In English Literature classes we would read the ballads. I remember reading 'Thomas the Rhymer' then, at school." "Thomas the Rhymer" and other supernatural ballads, dressed up in Johnson's elaborate arrangements, became the backbone of Steeleye's repertoire, so much so that Carthy believes it is Johnson's personality, more than anyone else's, that has defined Steeleye Span.

Johnson, Kemp, Prior, Hart and Knight made a formidable band, and Steeleye's next two albums, Below the Salt (1972) and Parcel of Rogues (1973), are considered classics of the genre. For some staunch Steeleye fans, these two records have never been surpassed. Prior sees this as a transitional period, before drums re-entered the group's sound (only Hark! The Village Wait had featured drums), but after Kemp's percussive bass and Johnson's hard-edged rock guitar began exerting their influence. "Those two albums were very distinctive, very different from what had gone before and what came afterwards," she says. "I think Bob and Rick having an essentially pure rock n roll [background], gave it a different slant completely from what had gone before. It's a different balance and crossover. We were starting to move towards a more accessible rock format, rock and roll as it were."

Johnson, Kemp, Prior, Hart and Knight made a formidable band, and Steeleye's next two albums, Below the Salt (1972) and Parcel of Rogues (1973), are considered classics of the genre. For some staunch Steeleye fans, these two records have never been surpassed. Prior sees this as a transitional period, before drums re-entered the group's sound (only Hark! The Village Wait had featured drums), but after Kemp's percussive bass and Johnson's hard-edged rock guitar began exerting their influence. "Those two albums were very distinctive, very different from what had gone before and what came afterwards," she says. "I think Bob and Rick having an essentially pure rock n roll [background], gave it a different slant completely from what had gone before. It's a different balance and crossover. We were starting to move towards a more accessible rock format, rock and roll as it were."In addition to this toughening up of Steeleye's sound, their material on those two albums was stronger than ever. Johnson's arrangement of the ballad "King Henry" from Below the Salt was in his words "my first deliberate, conscious attempt to go into the ballad collections, find one and try and arrange it in some way and make it rocky." It is a long song that tells a strong, simple story, broken up into several parts by changes in rhythm, all handled beautifully by the band and particularly by Johnson and Kemp. Other classics from Below the Salt include the pastoral ditties "Rosebud in June" and "Spotted Cow" and the group's rendition of "John Barleycorn," one of the best-loved of Britain's traditional songs.

Despite the strength of the "folk" material, Below the Salt's runaway hit was "Gaudete," a Latin chant celebrating the birth of Christ, sung a capella in five-part harmony. The single was Steeleye's first big hit, reaching number fourteen in the British charts. "We were on Top of the Pops with it," Prior exclaims. "It was extraordinary! As it was then, which was kind of like all tits and bums and stuff, to go on to sing this Latin chant was extraordinary!" Not everyone loved it, however. "When we recorded it, the engineer loathed it. Absolutely hated it. So that's why it's got a very long fade in and a very long fade out," Prior explains.

Despite the strength of the "folk" material, Below the Salt's runaway hit was "Gaudete," a Latin chant celebrating the birth of Christ, sung a capella in five-part harmony. The single was Steeleye's first big hit, reaching number fourteen in the British charts. "We were on Top of the Pops with it," Prior exclaims. "It was extraordinary! As it was then, which was kind of like all tits and bums and stuff, to go on to sing this Latin chant was extraordinary!" Not everyone loved it, however. "When we recorded it, the engineer loathed it. Absolutely hated it. So that's why it's got a very long fade in and a very long fade out," Prior explains.

Also on Parcel Of Rogues, Prior showed her commitment to more worldly concerns in her arrangement of "The Weaver and the Factory Maid," which, she says, "is a song about change, you see. How different generations respond to change. In 'Weaver,' the young man thinks [the factory] is quite good 'cause there's all these girls, and the old man thinks it's terrible because the whole trade is going downhill. And those are not attitudes that have changed." In fact, the older generation's rejection of new technologies while youngsters enjoy their liberating qualities was a feature of the electric folk movement in Britain, out of which Steeleye Span arose, making the song a sort of analogy for Steeleye itself.

Also on Parcel Of Rogues, Prior showed her commitment to more worldly concerns in her arrangement of "The Weaver and the Factory Maid," which, she says, "is a song about change, you see. How different generations respond to change. In 'Weaver,' the young man thinks [the factory] is quite good 'cause there's all these girls, and the old man thinks it's terrible because the whole trade is going downhill. And those are not attitudes that have changed." In fact, the older generation's rejection of new technologies while youngsters enjoy their liberating qualities was a feature of the electric folk movement in Britain, out of which Steeleye Span arose, making the song a sort of analogy for Steeleye itself.A single song on Parcel Of Rogues featured a guest drummer. Soon, at the urging of Rick Kemp, the band began looking for a full-time drummer to fulfill its rock and roll destiny. They came up with Nigel Pegrum. "It took us a while to find Nigel," Prior remembers, "because we wanted someone who was quite musical. He played flute as well. He came in on that level as well, so we didn't have to have drums all the time, although it worked out that that's mostly what he did."

With Pegrum in tow, Steeleye Span became the "classic" lineup that would reach dizzying heights of popularity and sobering depths of disarray, a lineup that would disband, regroup, and fragment again.

But Steeleye would survive.