Do You Know Jack?

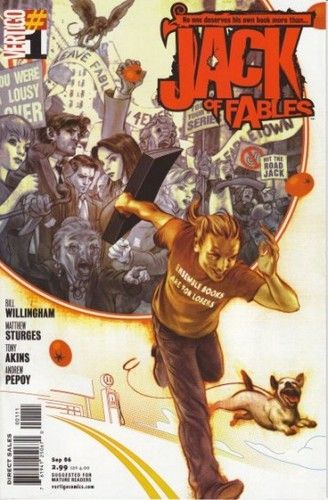

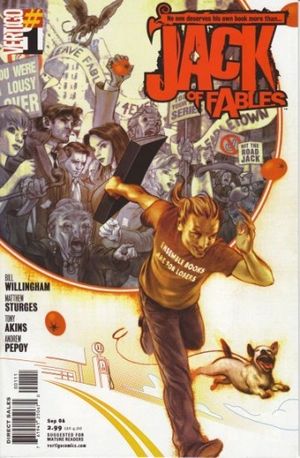

Bill Willingham’s multiple-Eisner-award-winning comic book series, Fables, began with a young man urging a New York cab driver to go faster. Readers were soon introduced to the near-frantic passenger: Jack, a former fairy-tale hero who had been expelled from his homeland by the mysterious “Adversary,” and who was living in exile in New York City. Jack was joined in his predicament by such fairy-tale regulars as Beauty and the Beast, Snow White, the Frog Prince, the Three Little Pigs, and the Big Bad Wolf. Through multiple storylines, Jack remained one of the series’ most compelling characters, and eventually spun off into his own comic series, Jack of Fables, in which he was revealed to be not only the nursery-rhyme star of “Little Jack Horner” and “Jack Be Nimble,” but also the sword-wielding hero of “Jack and the Beanstalk” and “Jack the Giant-Killer.”

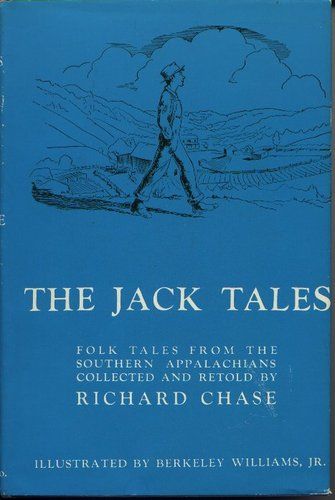

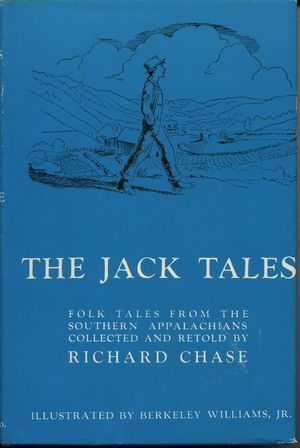

Bill Willingham’s multiple-Eisner-award-winning comic book series, Fables, began with a young man urging a New York cab driver to go faster. Readers were soon introduced to the near-frantic passenger: Jack, a former fairy-tale hero who had been expelled from his homeland by the mysterious “Adversary,” and who was living in exile in New York City. Jack was joined in his predicament by such fairy-tale regulars as Beauty and the Beast, Snow White, the Frog Prince, the Three Little Pigs, and the Big Bad Wolf. Through multiple storylines, Jack remained one of the series’ most compelling characters, and eventually spun off into his own comic series, Jack of Fables, in which he was revealed to be not only the nursery-rhyme star of “Little Jack Horner” and “Jack Be Nimble,” but also the sword-wielding hero of “Jack and the Beanstalk” and “Jack the Giant-Killer.” What makes Jack such a Protean, wide-ranging hero? Folklore aficionados would not be surprised at such multiplication; the landmark 1943 anthology The Jack Tales, by Richard Chase, presents Jack as the quintessential American hero. But even before that, in the world of English-language fairy tales, Jack was a uniquely popular protagonist, the central figure in a wide variety of adventure tales, wherever English was spoken. From John O’ Groats to Land’s End, from Belfast to Cork, and most especially from Canada to the southern Appalachians, Jack is our favorite folktale hero, a clever, lucky, generous, and well-endowed Everyman.

Of course, there isn’t just one Jack. In some tales, Jack is an only child who lives alone with his mother. In others, he has two older brothers, Will and Tom, and two living parents. In still others, his mother is dead, and he is at the mercy of an evil stepmother. Jack is sometimes a fool, sometimes average, sometimes the cleverest boy in town. Traditional storytellers have their own ways of dealing with Jack’s multiple lives; some of them try to reconcile their stories to provide a clear biography for Jack, while others embrace his variety. Folklorist Bill Nicolaisen (1978: 36) once asked North Carolina narrator Marshall Ward why Jack seems to get married over and over again in the stories. Ward answered, “This ain’t the same Jack. These stories are one hundred, two hundred, three hundred years apart.”

Of course, there isn’t just one Jack. In some tales, Jack is an only child who lives alone with his mother. In others, he has two older brothers, Will and Tom, and two living parents. In still others, his mother is dead, and he is at the mercy of an evil stepmother. Jack is sometimes a fool, sometimes average, sometimes the cleverest boy in town. Traditional storytellers have their own ways of dealing with Jack’s multiple lives; some of them try to reconcile their stories to provide a clear biography for Jack, while others embrace his variety. Folklorist Bill Nicolaisen (1978: 36) once asked North Carolina narrator Marshall Ward why Jack seems to get married over and over again in the stories. Ward answered, “This ain’t the same Jack. These stories are one hundred, two hundred, three hundred years apart.” Lucky Jack

Despite the divergent storylines and life circumstances we find in Jack Tales, folklorists have found common ground in most of them: Jack is one lucky customer. C. Paige Gutierrez (1978) identified three types of luck in North Carolina Jack Tales, and these seem to apply to other Jacks as well. Sometimes, Jack’s luck is mere chance, as in Andrew Stewart’s Scottish version of “Jack and the Three Feathers” (Various Artists 2000). In this long magic tale, Jack throws a feather in the air and follows it to its landing, there to discover a magic frog who helps him win the kingdom. The feather seems to have been directed by pure chance.

In other stories, Jack’s luck is linked to his virtue, as in Edna Carter’s Virginia version of “Jack and the Beggar” (Perdue 1987: 50-51). In this story, Jack is kind to a beggar and a stray dog, who turn out to be the ghosts of a rich man and his pet. The ghosts lead him to the rich man’s hidden treasure, explaining that they chose him “because he’d took in a poor beggar an’ a homeless dog.” Is Jack lucky in this tale? Certainly; after all, of all people, the ghosts decide to test him. But Jack is also kindhearted, and this is what wins the day.

Still other times, Jack’s luck is helped along by skill and cleverness. In Ray Hicks’s (1977) North Carolina version of “Jack and the Three Steers,” for example, Jack is ordered by a gang of vicious thieves to steal three steers, on pain of death. Jack looks around for tools to help him in his task. His luck goes only so far; all he finds are a short hank of rope and an abandoned slipper. Of course, the real fun of the tale is in his cleverness; listeners thrill to hear how the ingenious Jack uses these seemingly useless items to trick a farmer into abandoning his cattle.

Storytellers, too, recognize Jack’s constant good luck. In 1939, Tennessee tale-teller Sam Harmon remarked to collector Herbert Halpert (1943: 187), “if I was to name my boys over, I’d name all of them Jack. I never knowed a Jack but what was lucky.”

The Blood of an Englishman: Jack Tales and Anglo Roots

In some ways, Jack’s popularity is not unique to English. Jack is a diminutive of John, and folktale Jack thus shares his name with German Hans or Hansel (derived from “Johannes,” German for John) and French Ti Jean, literally “petit Jean,” or “little John.” Both of these are common folktale protagonists, and both have emerged into popular culture; to pick only two of numerous examples, the playwright and Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott wrote a play called Ti Jean and his Brothers (Harrison 1989: 91-153), and Engelbert Humperdinck’s opera Hansel and Gretel is a popular Christmas staple. These connections between international versions of Jack were not unknown to ordinary people; the Franco-American writer Jean-Louis Kerouac was nicknamed “Ti Jean” in French, “Jack” in English.

Similarly, Spanish tales about “Juan” and Russian stories about “Ivan” share roots with Jack. Even a unique, iconic character like Pinocchio has some European Jack in him; Folklorist Jack Zipes (1999: 145) tells us that Carlo Collodi’s 1882 novel, which introduced the famous puppet, was written after Collodi completed a number of books about “Giannettino,” or “little John,” and was based on his reading of Jack Tales.

Clearly, the Anglo Jack is just one facet of a wider European tradition. However, in other ways, Jack is especially English, and deeply embedded in the psyche of English-speakers. The very name “Jack,” for example, is English. It’s not, as some think, derived from French “Jacques,” but more likely comes from the Middle English “Jankyn,” a diminutive form of “John.” The Scots language grew from the same Anglo-Saxon roots as English, so Jack exists in Scotland too, sometimes as Jock or Jeck. The name has taken many forms and many meanings in English and Scots, coming to mean a man in general (“man-jack,” “jack-of-all-trades”), a worker (lumberjack, Jack Tar), a useful tool (jackknife, hydraulic jack), and a fool (jackanapes, jackass). As a diminutive of one of the most often used English names, it suggests both commonness and humility, and is thus a name for Everyman, much like the later legal nickname, John Doe. However, “Jack” combines its commonness and humbleness with clearly Anglo-Saxon ancestry; after all, his most famous opponent, the giant, smells the blood not of an Everyman, but of an Englishman.

From Farm-Boy to Giant-Killer: Early Jack Tales

Jack’s tradition goes back surprisingly far; the earliest Jack Tale is genuinely medieval, and was written down in the fifteenth century. In this story, known originally as “Jack and His Stepdame,” and later as “The Friar and the Boy” (Furrow 1985: 67-153), Jack is a farmer’s son whose stepmother underfeeds him, and wants to send him into indentured servitude. Jack’s father compromises by sending him to a far pasture to watch the cattle. There Jack meets a hungry beggar, with whom he shares his meager lunch. In return, the beggar offers him three gifts. Jack asks for a bow and arrows; the beggar gives him a magical bow and arrows, which never miss their mark. Jack asks for a pipe, so that he might have music and be merry. The beggar gives him a magical pipe, which compels all who hear it to dance. Jack says that these two gifts are enough, but the beggar insists on a third. Jack remembers the look of hatred that comes to his stepmother’s face whenever she sees him eat; he wishes that, every time she looks at him that way, she will fart so loudly that everyone will hear her. The beggar promises to grant his wish, and departs.

Jack’s tradition goes back surprisingly far; the earliest Jack Tale is genuinely medieval, and was written down in the fifteenth century. In this story, known originally as “Jack and His Stepdame,” and later as “The Friar and the Boy” (Furrow 1985: 67-153), Jack is a farmer’s son whose stepmother underfeeds him, and wants to send him into indentured servitude. Jack’s father compromises by sending him to a far pasture to watch the cattle. There Jack meets a hungry beggar, with whom he shares his meager lunch. In return, the beggar offers him three gifts. Jack asks for a bow and arrows; the beggar gives him a magical bow and arrows, which never miss their mark. Jack asks for a pipe, so that he might have music and be merry. The beggar gives him a magical pipe, which compels all who hear it to dance. Jack says that these two gifts are enough, but the beggar insists on a third. Jack remembers the look of hatred that comes to his stepmother’s face whenever she sees him eat; he wishes that, every time she looks at him that way, she will fart so loudly that everyone will hear her. The beggar promises to grant his wish, and departs.Using the pipe, which causes his father’s cattle to dance along behind him, Jack easily herds the cattle back to their pens, and heads home for supper. Jack’s father invites him to eat, whereupon the stepmother glares at him:

Then she stared in his face

And soon let go such a blast

That she made them all aghast

That were within that place.

They all laughed at such a game;

The wife instead turned red in shame.

(Furrow 1985: 109-110; my translation)

Soon, Jack's stepmother retires for the night, humiliated. The next day, a mendicant friar arrives. Jack’s stepmother complains about Jack, and the friar seeks him out in the fields and threatens to beat him. Jack promises that to make amends he will shoot a bird for the friar’s dinner. Using his magic bow, he shoots a bird and causes it to fall in a briar thicket. When the friar enters the thicket, Jack begins playing the pipe. This causes the friar to leap and dance, so that he is horribly scratched by the thorns. Jack eventually stops playing and lets the friar go.

The friar returns to Jack’s father and stepmother. He reports what Jack has done, and the father demands to hear the pipe. The friar, fearing the music, begs to be tied up, and is tied to a post. Jack begins playing, the whole household begins to dance, and Jack carefully leads them all outside. Soon, all the townspeople are dancing. Everyone has a good time, except the friar, who further injures himself by banging his head against the post, and the stepmother, who cannot help glaring at Jack, and farting. At the end of the dance, the father is amused, the stepmother is chastened, the friar is bruised, and Jack lives happily ever after.

The friar returns to Jack’s father and stepmother. He reports what Jack has done, and the father demands to hear the pipe. The friar, fearing the music, begs to be tied up, and is tied to a post. Jack begins playing, the whole household begins to dance, and Jack carefully leads them all outside. Soon, all the townspeople are dancing. Everyone has a good time, except the friar, who further injures himself by banging his head against the post, and the stepmother, who cannot help glaring at Jack, and farting. At the end of the dance, the father is amused, the stepmother is chastened, the friar is bruised, and Jack lives happily ever after.It may be surprising to many people to encounter fart jokes in Jack tales; most such tales have been cleaned up for publication. But the oral tradition leaves no doubt that Jack could be both scatological and sexual; Vance Randolph, for example, found bawdy versions of Jack tales alive and well in Missouri and Arkansas in the 1940s (Randolph 1976: 18-19, 47-49). Even the North Carolina tradition documented by Richard Chase had its moments; the story Chase called “Hardy Hard-Head,” was, storyteller Ray Hicks insisted, traditionally called “Hardy Hard-Ass,” and featured a character whose giant, rock-tough posterior served as a shield and a battering ram (McCarthy 1994: 10-26). Another Jack tale was known simply as “Stiff Dick” (Harmon 2001: 1-6), but the character who calls himself “Stiff Dick” is actually named Jack! These off-color touches speak to a long tradition of bawdy Jack tales that folklorist Joseph Sobol (1992: 98) calls “Fabliau Jack,” after a genre of medieval bawdry favored by Chaucer and Boccaccio. (Indeed, there are several bawdy characters named "Jankyn" in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, suggesting that the great poet might himself have been familiar with Jack tales.)

“Jack and His Stepdame” is as much fairy tale as fabliau, however, and its fairy-tale elements reveal some of Jack’s mythical meaning. Jack’s act of kindness results in three gifts from a magical donor—a typical fairy-tale beginning. The gifts include a magical bow, which is a limitless source of food, and a magical musical instrument, which is a limitless source of art. Jack thus returns home with both physical and spiritual nourishment for his community. After the supper and dance, Jack’s father says he has not had a better time in seven years, and throughout the community, “every man was of good cheer.” Jack can keep his community not only fed, but happy.

The importance of this seems to be understood by the characters in the story. Jack, for example, initially refuses the third gift, since physical nourishment and happiness are enough for anyone, but the beggar presses him. Interestingly, this third gift, the one Jack initially doesn’t want or need, transforms the tale from a pure fairy tale into a farcical fabliau. (In all of Randolph’s bawdy tales, meanwhile, Jack has an unusually large penis, another common element in fabliaux; this suggests another way in which “Fabliau Jack” is a provider of pleasure.)

The next stage in Jack’s development brings him further into the realms of Faerie. “Jack the Giant-Killer” was first printed before 1708. More tellingly, the giant’s rhyme, “fee fi fo fum,” is much older, having been quoted by Thomas Nashe in 1596 (Opie 1974: 48). It seems very likely from this that some version of the tale predates the eighteenth century.

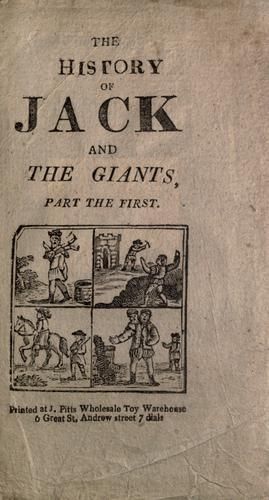

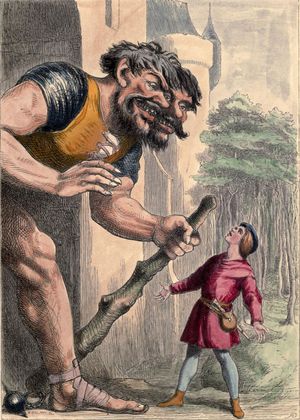

“Jack the Giant-Killer,” or to give it its early literary name, The History of Jack and the Giants (Ashton 1882: 184-192), is an episodic tale in which Jack travels around Britain, especially Cornwall and Wales, killing giants. Some he dispatches with mere violence, for example, by digging a pit trap and then taking a pickaxe to the giant’s head. Others, he defeats with clever trickery, as when he fools a hapless giant by apparently cutting open his stomach; the giant attempts to compete and, in the words of the chapbook, “ripped up his own belly, from the bottom to the top, and out dropped his tripes and his troly bags, so that hur fell down for dead.” (Green 2007: 10)

“Jack the Giant-Killer,” or to give it its early literary name, The History of Jack and the Giants (Ashton 1882: 184-192), is an episodic tale in which Jack travels around Britain, especially Cornwall and Wales, killing giants. Some he dispatches with mere violence, for example, by digging a pit trap and then taking a pickaxe to the giant’s head. Others, he defeats with clever trickery, as when he fools a hapless giant by apparently cutting open his stomach; the giant attempts to compete and, in the words of the chapbook, “ripped up his own belly, from the bottom to the top, and out dropped his tripes and his troly bags, so that hur fell down for dead.” (Green 2007: 10)The History of Jack and the Giants is set “in the reign of King Arthur.” This has prompted several scholars, most recently Thomas Green (2007: 1-4), to point out similarities between Jack’s exploits and those of the mythical king. In ancient Cornish and Welsh mythology, Arthur slew Britain’s last remaining giants, but in the eighteenth Century, Jack replaced him as giant-killer. Jack’s giant-slaying exploits are strikingly similar to Arthur’s, too, prompting Carl Lindahl (1994: xv) to ask: “Has the legendary British king traded his crown for a hoe and become a working-class hero?” It’s a hard question to answer, but the connection seems to have been deliberate on the part of the chapbook’s author.

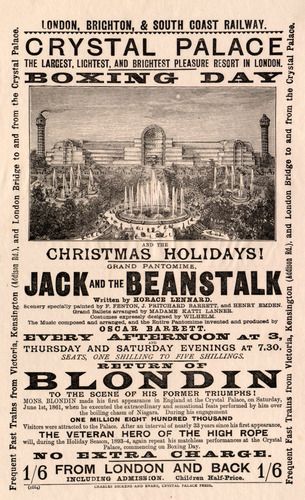

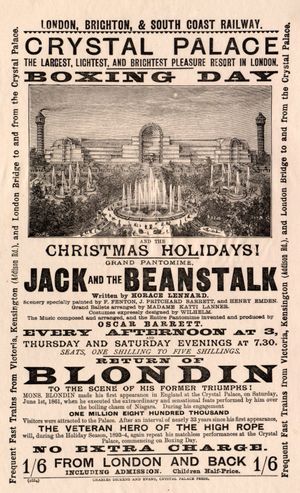

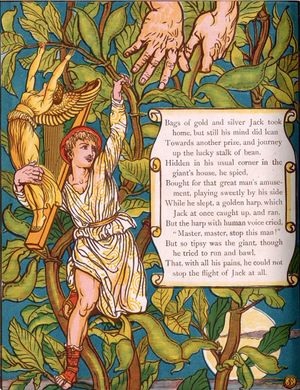

At around the same time as The History of Jack and the Giants, another tale was making the rounds in the English oral tradition. The 1734 edition of Round About Our Coal-Fire: or Christmas Entertainments contains a brief discussion of “Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean,” which from its plot is clearly a version of “Jack and the Beanstalk” (Opie 1974: 162). (Interestingly, “Jack and the Beanstalk” was later a popular Christmas pantomime; this shows that its association with the holidays seems to have begun early.) If The History of Jack and the Giants places Jack in a mythical time of Arthur, “Jack and the Beanstalk” is a full-blown tale of faerie, where Jack leaves the ordinary England for an enchanted land in the clouds, in which he slays a giant, and from which he brings back magic gifts. It’s a classic tale that most people know: Jack, who is believed to be a silly and impractical boy, trades his family’s cow for some magic beans. His mother believes he has been cheated, and throws the beans out the window. During the night, a giant beanstalk grows up to the sky. Jack climbs the beanstalk three times, each time raiding a giant’s castle; he steals a bag of gold, a goose or hen that lays golden eggs, and a harp that plays by itself. On Jack’s first two raids, the giant’s wife saves him, but on the third, he is pursued by the giant. He chops down the beanstalk, the giant is killed, and Jack and his mother live happily ever after.

At around the same time as The History of Jack and the Giants, another tale was making the rounds in the English oral tradition. The 1734 edition of Round About Our Coal-Fire: or Christmas Entertainments contains a brief discussion of “Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean,” which from its plot is clearly a version of “Jack and the Beanstalk” (Opie 1974: 162). (Interestingly, “Jack and the Beanstalk” was later a popular Christmas pantomime; this shows that its association with the holidays seems to have begun early.) If The History of Jack and the Giants places Jack in a mythical time of Arthur, “Jack and the Beanstalk” is a full-blown tale of faerie, where Jack leaves the ordinary England for an enchanted land in the clouds, in which he slays a giant, and from which he brings back magic gifts. It’s a classic tale that most people know: Jack, who is believed to be a silly and impractical boy, trades his family’s cow for some magic beans. His mother believes he has been cheated, and throws the beans out the window. During the night, a giant beanstalk grows up to the sky. Jack climbs the beanstalk three times, each time raiding a giant’s castle; he steals a bag of gold, a goose or hen that lays golden eggs, and a harp that plays by itself. On Jack’s first two raids, the giant’s wife saves him, but on the third, he is pursued by the giant. He chops down the beanstalk, the giant is killed, and Jack and his mother live happily ever after.  Various psychoanalytical interpretations of “Jack and the Beanstalk” (e.g. Bettelheim 1976) have suggested that the beanstalk is a phallic image and the tale is essentially about sexual differentiation from one’s parents. The giant is an evil father-figure who has destroyed and replaced Jack’s true father—a typical Oedipal fantasy. The giant’s wife is a fantasy aspect of Jack’s mother, which explains why she helps him to escape her evil husband. In the end, Jack conquers the evil aspects of his father, and in so doing transforms his mother from a woman who must reject his magic by throwing out the beans, into one who can partake of the gifts he brings back. How does Jack reintegrate his family? By destroying his father’s phallus—or, at least, by destroying its hold over him.

Various psychoanalytical interpretations of “Jack and the Beanstalk” (e.g. Bettelheim 1976) have suggested that the beanstalk is a phallic image and the tale is essentially about sexual differentiation from one’s parents. The giant is an evil father-figure who has destroyed and replaced Jack’s true father—a typical Oedipal fantasy. The giant’s wife is a fantasy aspect of Jack’s mother, which explains why she helps him to escape her evil husband. In the end, Jack conquers the evil aspects of his father, and in so doing transforms his mother from a woman who must reject his magic by throwing out the beans, into one who can partake of the gifts he brings back. How does Jack reintegrate his family? By destroying his father’s phallus—or, at least, by destroying its hold over him.This interpretation may reveal some of Jack’s meanings. However, Jack also has deeper mythical meanings that resonate beyond the psychological. Jack’s mythical nature is that of the explorer of other realms, and the slayer of ogres, not just for his own sake but for his community’s. As Charles T. Davis (1978) has recognized, Jack is an “archetypal hero.” Like Prometheus stealing fire from Zeus, Jack finds a magical giant in the sky and brings back his treasures. The first time, he brings back only a finite bag of gold, but on his subsequent raids he carries off apparently limitless resources: a goose that lays golden eggs and a harp that sings beautiful music. These gifts, like the bow and the pipe of “Jack and His Stepdame,” clearly represent limitless physical and spiritual nourishment for his community. When he has them, in Flora Annie Steel’s (1918: 109) telling of the tale, “every one was quite happy,” and Jack himself “became quite a useful person.”

In these three early Jack tales, then, we have the germ of Jack’s mythical persona. In “Jack and his Stepdame,” he is a trickster figure who brings back physical and spiritual sustenance for himself and his community. In “Jack and the Beanstalk,” this same theme is made more explicit, since the tale begins with poverty for the family, and ends with abundance. And in “Jack the Giant-Killer,” Jack makes the land safe for his community and civilization, destroying the monsters of the encroaching otherworld who seek “the blood of an Englishman.” Jack is the provider, protector and defender of his community, using luck and cleverness, kindness and trickery, to improve the lives of his people.

In these three early Jack tales, then, we have the germ of Jack’s mythical persona. In “Jack and his Stepdame,” he is a trickster figure who brings back physical and spiritual sustenance for himself and his community. In “Jack and the Beanstalk,” this same theme is made more explicit, since the tale begins with poverty for the family, and ends with abundance. And in “Jack the Giant-Killer,” Jack makes the land safe for his community and civilization, destroying the monsters of the encroaching otherworld who seek “the blood of an Englishman.” Jack is the provider, protector and defender of his community, using luck and cleverness, kindness and trickery, to improve the lives of his people. "It Takes Jack to Live": Jack Seeks His Fortune

Like Jack himself, Jack Tales soon went out to seek their fortune, traveling to the places where English people settled. When English-speakers crossed the ocean, Jack Tales went with them.

Precisely when Jack Tales came to America will never be determined for sure. Since at least some Jack Tales existed as early as the fifteenth century, they could have made the journey with the earliest English colonists, but they do not appear in the American historical record until the eighteenth century; Dr. Joseph Doddridge (1769-1826) wrote that, before 1783, Jack Tales were known in what was then western Virginia:

Dramatic narrations, chiefly concerning Jack and the giant, furnished our young people with another source of amusement during their leisure hours. Many of these tales were lengthy, and embraced a considerable range of incident. Jack, always the hero of the story, after encountering many difficulties, and performing many great achievements, came off conqueror of the giant.… Civilization has, indeed, banished the use of those ancient tales of romantic heroism; but what then? It has substituted in their place the novel and romance. (Doddridge 1912: 124)

Dramatic narrations, chiefly concerning Jack and the giant, furnished our young people with another source of amusement during their leisure hours. Many of these tales were lengthy, and embraced a considerable range of incident. Jack, always the hero of the story, after encountering many difficulties, and performing many great achievements, came off conqueror of the giant.… Civilization has, indeed, banished the use of those ancient tales of romantic heroism; but what then? It has substituted in their place the novel and romance. (Doddridge 1912: 124)Of course, Doddridge need not have worried about Jack. The tales have continued to be told in America, until this very day. The heartland of Jack Tales seems to have been the southern Appalachian Mountains, but the tales are found wherever the settlers went, including New York, North Carolina, Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, Maryland, Missouri, and Pennsylvania (Lindahl 1994: xxi). As Doddridge noted, they contain a wide range of incidents, with Jack sailing in a land-and-water ship, seducing king’s daughters, stealing money and cattle, faking his own death, and meeting and defeating giants, ghosts, robbers, unicorns, wild boar, and even Death and the Devil.

Scholars have tried to determine what makes American Jack different from his British and Irish counterparts. W.F.H. Nicolaisen (1978) concludes that British Jack traditions were broad enough that no significant aspects of American Jack are original to America. Carl Lindahl (1994), on the other hand, discovers differences in emphasis: American Jack is far less likely to use magic, for example, and relies instead more on cleverness and his wits. He also finds that, while English Jack is often a poor peasant who is hostile to the wealthier classes, American Jack accepts his place in the social order and often works for and with the wealthy, hoping, of course, to become wealthy himself. Meanwhile, Julie Henigan discovers that in America, Jack is likely to end the tale completely independent of his original household, living in a new place with a family of his own. Irish Jack, on the other hand, returns to his homeplace. These differences reflect the various norms within each community where Jack is found.

In fact, Jack reflects the community’s norms and its ideals, and is often perceived to be the quintessential member the community, whatever that community may be. Among the “Travellers” of Scotland, who live a nomadic life similar to gypsies, Jack is a figure to be idealized and emulated. Duncan Williamson, a great Traveller storyteller, explained, “Jack was the great man. They looked up tae him. […] They visualized themsels as Jack” (McDermitt 1979: 144). In much the same way, on the island of Newfoundland, Jack is seen as a perfect Newfoundlander. “We always felt Jack is a quintessential Newfoundland guy,” theater director Andy Jones told the Memorial University Gazette. “He has great survival instincts and at the end he does well because he kind of figures out the lay of the land.” (Fürst 2009) For traditional Appalachian farming-folk, too, Jack is an empowering example. The late, great Jack Tale teller Ray Hicks, of Beech Mountain, North Carolina, once told Barbara McDermitt (1983: 9), “Jack ain’t dead. He’s a-livin’. Jack can be anybody. Like I tell ’em sometimes, I’m Jack. Now I ain’t done everything Jack has done in the tales, but still I’ve been Jack in a lot of ways. It takes Jack to live.”

In fact, Jack reflects the community’s norms and its ideals, and is often perceived to be the quintessential member the community, whatever that community may be. Among the “Travellers” of Scotland, who live a nomadic life similar to gypsies, Jack is a figure to be idealized and emulated. Duncan Williamson, a great Traveller storyteller, explained, “Jack was the great man. They looked up tae him. […] They visualized themsels as Jack” (McDermitt 1979: 144). In much the same way, on the island of Newfoundland, Jack is seen as a perfect Newfoundlander. “We always felt Jack is a quintessential Newfoundland guy,” theater director Andy Jones told the Memorial University Gazette. “He has great survival instincts and at the end he does well because he kind of figures out the lay of the land.” (Fürst 2009) For traditional Appalachian farming-folk, too, Jack is an empowering example. The late, great Jack Tale teller Ray Hicks, of Beech Mountain, North Carolina, once told Barbara McDermitt (1983: 9), “Jack ain’t dead. He’s a-livin’. Jack can be anybody. Like I tell ’em sometimes, I’m Jack. Now I ain’t done everything Jack has done in the tales, but still I’ve been Jack in a lot of ways. It takes Jack to live.”Quite a Useful Person: Jack in Literature and Popular Culture

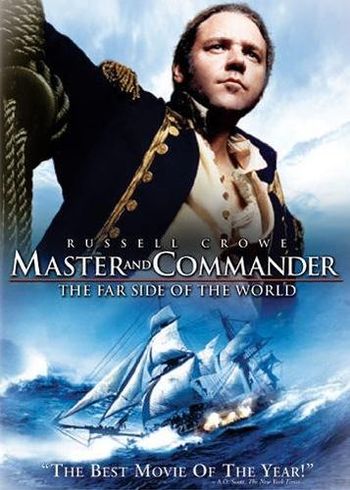

Given the popularity of Jack, it’s no surprise to see him adapted and used in many works of literature, both fantasy and otherwise. A recreational reader can encounter and enjoy Jack in a variety of guises. Who could doubt, for example, that there’s some folktale Jack in Patrick O’Brian’s flamboyant English naval Captain, Jack Aubrey? Aubrey is a giant-killer who repeatedly defeats massive men-of-war with small, outgunned sloops and frigates, using cleverness and trickery. Aubrey’s escapes are narrow and his exploits are sometimes fantastic; in one memorable sequence (O’Brian 1972: 102-113), he is forced to traverse most of France disguised as a bear. But like folktale Jack, he perseveres, venturing into the jaws of danger to bring back the secrets of Napoleon (“The Corsican Ogre”), with the help of his friend, the spy Stephen Maturin. Most tellingly, from the early days of his career, Aubrey is known as “Lucky Jack.”

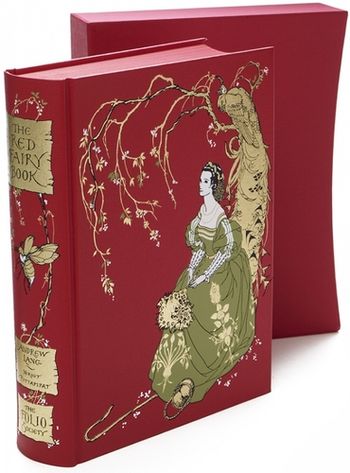

Given the popularity of Jack, it’s no surprise to see him adapted and used in many works of literature, both fantasy and otherwise. A recreational reader can encounter and enjoy Jack in a variety of guises. Who could doubt, for example, that there’s some folktale Jack in Patrick O’Brian’s flamboyant English naval Captain, Jack Aubrey? Aubrey is a giant-killer who repeatedly defeats massive men-of-war with small, outgunned sloops and frigates, using cleverness and trickery. Aubrey’s escapes are narrow and his exploits are sometimes fantastic; in one memorable sequence (O’Brian 1972: 102-113), he is forced to traverse most of France disguised as a bear. But like folktale Jack, he perseveres, venturing into the jaws of danger to bring back the secrets of Napoleon (“The Corsican Ogre”), with the help of his friend, the spy Stephen Maturin. Most tellingly, from the early days of his career, Aubrey is known as “Lucky Jack.” Folktale Jack is also a likely influence on the characters of Bilbo and Frodo Baggins, in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. The Hobbits were Tolkien’s stand-ins for the English middle-class (Shippey 2000: 9), and as we have seen, Jack is the English everyman who becomes a hero. Bilbo’s recruitment as a reluctant burglar, which starts his adventures in The Hobbit, seems to come from “The Master Thief,” commonly told as a Jack Tale in English (e.g. Davis 1992: 119). In his notes on The Hobbit, Douglas Anderson (Tolkien 2002: 73-83) points out that the scene in which Bilbo, with his magical helper Gandalf, tricks three trolls into staying out until sunrise, turning them to stone, is reminiscent of the Grimms’ “The Brave Little Tailor.” This is quite true, but it’s also true that that tale was known in English, as a Jack Tale (e.g. Harmon 2001). Meanwhile the trolls’ names, “Bert, William and Tom,” evoke Jack’s brothers Tom and Will. “Old Weatherbeard,” another Jack Tale, contains the very Tolkienian image of a magical ring placed among the embers of a fireplace. We know that Tolkien knew these tales; in the essay “On Fairy Stories,” he discussed the importance of Andrew Lang’s series of colored Fairy Books, in particular The Red Fairy Book, which influenced him profoundly as a child (Tolkien 1966: 39-41). The Red Fairy Book contains “Jack and the Beanstalk,” “The Master Thief,” and “Old Weatherbeard,” while its predecessor, The Blue Fairy Book, contains “Jack the Giant-Killer” and “The Brave Little Tailor.”

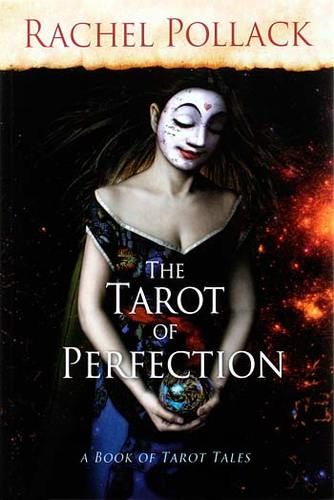

Folktale Jack is also a likely influence on the characters of Bilbo and Frodo Baggins, in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. The Hobbits were Tolkien’s stand-ins for the English middle-class (Shippey 2000: 9), and as we have seen, Jack is the English everyman who becomes a hero. Bilbo’s recruitment as a reluctant burglar, which starts his adventures in The Hobbit, seems to come from “The Master Thief,” commonly told as a Jack Tale in English (e.g. Davis 1992: 119). In his notes on The Hobbit, Douglas Anderson (Tolkien 2002: 73-83) points out that the scene in which Bilbo, with his magical helper Gandalf, tricks three trolls into staying out until sunrise, turning them to stone, is reminiscent of the Grimms’ “The Brave Little Tailor.” This is quite true, but it’s also true that that tale was known in English, as a Jack Tale (e.g. Harmon 2001). Meanwhile the trolls’ names, “Bert, William and Tom,” evoke Jack’s brothers Tom and Will. “Old Weatherbeard,” another Jack Tale, contains the very Tolkienian image of a magical ring placed among the embers of a fireplace. We know that Tolkien knew these tales; in the essay “On Fairy Stories,” he discussed the importance of Andrew Lang’s series of colored Fairy Books, in particular The Red Fairy Book, which influenced him profoundly as a child (Tolkien 1966: 39-41). The Red Fairy Book contains “Jack and the Beanstalk,” “The Master Thief,” and “Old Weatherbeard,” while its predecessor, The Blue Fairy Book, contains “Jack the Giant-Killer” and “The Brave Little Tailor.”  Serious writers of fantasy continue to be inspired by Jack Tales. In her 2008 story collection, The Tarot of Perfection, Rachel Pollack includes several tales that recall Jack’s exploits. “The Fool, the Stick, and the Princess” is based upon the Tarot Fool, but also on the idea of the foolish youngest brother in folktales, a category that often includes Jack. Its title, and to some extent its plot, recall “The Ox, the Table and the Stick,” a common Jack Tale. One of the book’s central stories is “Simon Wisdom,” which begins with a young single man named Jack, who eventually marries and has a child named Simon. In his initial innocence, and his kindheartedness, Jack Wisdom is much like folktale Jack. The fact that he makes significant mistakes does not make him any less a Jack; by the end, he has redeemed himself, accepted a magical gift, and helped to save his son.

Serious writers of fantasy continue to be inspired by Jack Tales. In her 2008 story collection, The Tarot of Perfection, Rachel Pollack includes several tales that recall Jack’s exploits. “The Fool, the Stick, and the Princess” is based upon the Tarot Fool, but also on the idea of the foolish youngest brother in folktales, a category that often includes Jack. Its title, and to some extent its plot, recall “The Ox, the Table and the Stick,” a common Jack Tale. One of the book’s central stories is “Simon Wisdom,” which begins with a young single man named Jack, who eventually marries and has a child named Simon. In his initial innocence, and his kindheartedness, Jack Wisdom is much like folktale Jack. The fact that he makes significant mistakes does not make him any less a Jack; by the end, he has redeemed himself, accepted a magical gift, and helped to save his son. Pollack’s novel, Godmother Night, which won the 1997 World Fantasy Award, is based on several Fairy Tales, most notably “Godfather Death.” But Jack’s exploits also seem to be part of the mix. The central character of the novel is Jacqueline, who tries several versions of her name, including “Jack,” before settling on “Jaqe.” Jaqe’s very special relationship with Death recalls Jack’s interactions with Death in the Jack Tale “Soldier Jack” (Chase 1993: 172-179): like Jack, Jaqe tries to prevent those around her from dying, and like Jack she eventually must surrender to Death herself.

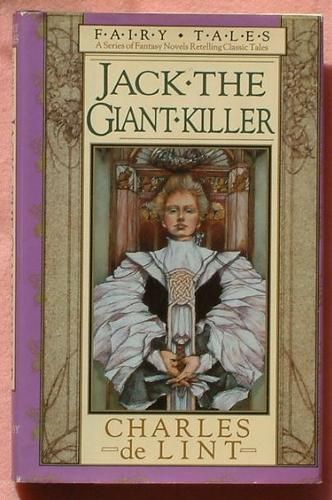

There are several superficial similarities between Godmother Night and an earlier Jack novel, Charles de Lint’s Jack the Giant Killer: both feature a posse of supernatural bikers, and the protagonists of both are named Jacqueline and Kate. In Jack the Giant-Killer, however, Jacky is explicitly recognized as Jack of the fairy tales. In fact, in de Lint’s realms of Faerie, “Jack” is not a name but a title; Jacky Rowan’s name is considered “a lucky name,” but not a prerequisite for her being “a Jack.” In the story, which occurs in the Faerie realm that exists alongside modern-day Ottawa, Jacky Rowan and Kate Hazel (a.k.a. Kate Crackernuts, another folktale reference) must protect the Faerie clan of Kinrowan against the Unseelie Court. But Jacky and Kate live in the mundane world, and must learn the ropes of Faerie as they go. Jacky behaves as a true Jack: she obtains magical gifts which she either uses for herself, or returns to their rightful owners; she rescues the Laird of Kinrowan’s daughter, whose protection spells are desperately needed by the clan; and, most tellingly, she kills several giants. In the end, Jacky takes up residence in a magical tower as the clan’s protector and provider. Jack the Giant-Killer, and its sequel, Drink Down the Moon, remain the most thorough fictional exploration of Jack’s mythic nature.

There are several superficial similarities between Godmother Night and an earlier Jack novel, Charles de Lint’s Jack the Giant Killer: both feature a posse of supernatural bikers, and the protagonists of both are named Jacqueline and Kate. In Jack the Giant-Killer, however, Jacky is explicitly recognized as Jack of the fairy tales. In fact, in de Lint’s realms of Faerie, “Jack” is not a name but a title; Jacky Rowan’s name is considered “a lucky name,” but not a prerequisite for her being “a Jack.” In the story, which occurs in the Faerie realm that exists alongside modern-day Ottawa, Jacky Rowan and Kate Hazel (a.k.a. Kate Crackernuts, another folktale reference) must protect the Faerie clan of Kinrowan against the Unseelie Court. But Jacky and Kate live in the mundane world, and must learn the ropes of Faerie as they go. Jacky behaves as a true Jack: she obtains magical gifts which she either uses for herself, or returns to their rightful owners; she rescues the Laird of Kinrowan’s daughter, whose protection spells are desperately needed by the clan; and, most tellingly, she kills several giants. In the end, Jacky takes up residence in a magical tower as the clan’s protector and provider. Jack the Giant-Killer, and its sequel, Drink Down the Moon, remain the most thorough fictional exploration of Jack’s mythic nature.Jack is a prominent character in two recent series of fantasy novels for kids: The Sisters Grimm by Michael Buckley, and Beyond the Spiderwick Chronicles by Tony DeTerlizzi and Holly Black. In the former, fairy-tale characters known as “everafters” live in exile in a town in upstate New York, watched over by Relda Grimm and her granddaughters, Sabrina and Daphne. In the series’ first novel, Jack, once a rich and famous giant-killer, now works at a big-and-tall men’s store. Bitter and angry about his reversal of fortune, he seems ready to help the girls when giants attack the town. As it turns out, however, the giants’ attacks are part of Jack’s plan to regain his status as a hero. Beyond the Spiderwick Chronicles contains a more modest and down-to-earth version of Jack, known as “NoSeeum Jack” because his eyesight is failing. In this series, it’s revealed that Jack’s giant-slaying is a hereditary role passed from father to son.

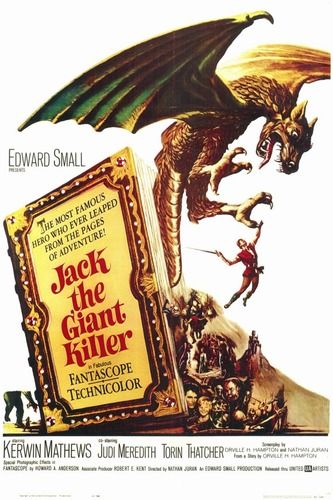

Jack has several times been adapted for the screen. Jack the Giant-Killer, a 1962 stop-motion epic, adds structure to Jack’s giant-killing exploits by creating a framing story about a princess captured and bewitched by the evil lord Pendragon. By contrast, Jack and the Beanstalk: The Real Story, a 2001 TV miniseries, begins with Jack’s modern descendant, and works its way backward to explain Jack’s original tale, with effects by Jim Henson’s Creature Shop. Both are available on DVD. There is also a big-budget film of Jack the Giant-Killer in production, with X-Men director Bryan Singer directing, actors such as Ewan McGregor and Stanley Tucci in supporting roles, and Nicholas Hoult as Jack.

Jack has several times been adapted for the screen. Jack the Giant-Killer, a 1962 stop-motion epic, adds structure to Jack’s giant-killing exploits by creating a framing story about a princess captured and bewitched by the evil lord Pendragon. By contrast, Jack and the Beanstalk: The Real Story, a 2001 TV miniseries, begins with Jack’s modern descendant, and works its way backward to explain Jack’s original tale, with effects by Jim Henson’s Creature Shop. Both are available on DVD. There is also a big-budget film of Jack the Giant-Killer in production, with X-Men director Bryan Singer directing, actors such as Ewan McGregor and Stanley Tucci in supporting roles, and Nicholas Hoult as Jack.Which brings us up to date, and back to Fables. Jack of Fables came to a violent end in 2011, when Jack Horner, transformed into a dragon by his own greed, and Jack Frost, his son and successor as Giant-Killer, come together in an epic battle. Both of them, and practically all of their many sidekicks, are killed. But Willingham leaves the door open for Jack to return, either as a ghost or as a resurrected Fable. Will Jack be back? Only time will tell.

These current explorations of Jack notwithstanding, the best way to experience Jack Tales is to listen to traditional storytellers; indeed, this is the only way to understand what these tales are like in their natural state. Obviously, the best way to do this is to find good local storytellers who know Jack Tales. If you can't find one, of course, you can listen to recordings; the discography lists several commercial recordings that are currently available. Also, the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. has many hours of Jack Tales by both traditional and revivalist storytellers, from the 1920s to today (see Harvey 2003 for details). So get yourself to a storyteller, pop in a CD, or visit the Library's Folklife Reading Room. Then close your eyes and listen.

If you're lucky, you'll get to hear a teller like the late Ray Hicks or his nephew Orville (or watch Ray in the film Fixin’ to Tell About Jack). A teller like Ray can transport you into the story much more completely than a book can. As Hicks’s other nephew, Frank Proffitt, once said (McCarthy 1994: 33), “he becomes Jack when he’s telling. And when I watch him, we both become Jack.”

Further Reading, Listening, and Viewing

Ashton, John. 1882. Chapbooks of the Eighteenth Century. London: Chatto and Windus.

Bettelheim, Bruno. 1976. The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales. Knopf: New York.

Davis, Charles. 1978. “Jack as Archetypal Hero.” North Carolina Folklore Journal, 26.2 134-140.

Doddridge, Joseph. 1912 [1824]. Notes on the Settlement and Indian Wars of the Western Parts of Virginia and Pennsylvania from 1763 to 1783 Inclusive, Together with a Review of the State of Society and Manners of the First Settlers of the West Country. With a Memoir of the Author by Narcissa Doddridge. Pittsburgh, PA: John Ritenour and William Lindsay.

Fürst, Bojan. “Spotlight on Alumni.” Memorial University Gazette online. Available from <http://www.mun.ca/gazette/issues/vol41no11/spotlight.php> Accessed 13 October, 2009

Green, Thomas. 2007. The Arthuriad, vol. 1. Available from <http://www.arthuriana.co.uk/arthuriad/Arthuriad_VolOne.pdf> Accessed 13 October, 2009

Guiterrez, Paige. 1978. “The Jack Tale: A definition of a folk tale sub-genre.” North Carolina Folklore Journal 12.2: 85-109

Halpert, Herbert. 1943. “Appendix.” In The Jack Tales by Richard Chase. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 183-188.

Henigan, Julie. 1987 “‘Mother Bake My Cake and Kill My Cock’: Social Structure and the Irish and American Jack Tales.” North Carolina Folklore Journal 34 2, 87-105.

Lindahl, Carl. 1994. “Introduction.” In Jack in Two Worlds, edited by William Bernard McCarthy. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

McCarthy, William Bernard, ed. 1994. Jack in Two Worlds. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

McDermitt, Barbara. 1979. “Duncan Williamson.” Tocher 34: 141-148

McDermitt, Barbara. 1983. “Storytelling and a Boy Named Jack.” North Carolina Folklore Journal 31: 3-22

Nicolaisen, W. F. H. 1978. “English Jack and American Jack.” Midwestern Journal of Language and Folklore 4-1: 27-36

Sobol, Joseph. 1992. “Jack of a Thousand Faces: The Jack Tales as an Appalachian Hero Cycle.” North Carolina Folklore Journal, 39:2, 77-108

Shippey, Tom. 2000. J.R.R. Tolkien, Author of the Century. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Tolkien, J.R.R. 1966. The Tolkien Reader. New York: Ballantine.

Tales and adaptations

Buckley, Michael. 2007. The Sisters Grimm: The Fairy-Tale Detectives. New York: Amulet Books.

Chase, Richard. 1943. The Jack Tales. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Davis, Donald. 1992. Jack Always Seeks His Fortune: Authentic Appalachian Jack Tales. Little Rock: August House.

De Lint, Charles. 1987. Jack the Giant Killer. New York: Ace Books.

DiTerlizzi, Tony, and Holly Black. 2007. The Nixie’s Song. New York: Simon and Schuster.

DiTerlizzi, Tony, and Holly Black. 2008. A Giant Problem. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Harrison, Paul Carter, ed. 1989. Totem Voices: Plays from the Black World Repertory. New York : Grove Press. [includes “Ti-Jean and his Brothers” by Derek Walcott]

Harmon, Samuel. 2001. “Stiff Dick.” Journal of Folklore Research 38 1-2: 3-6.

Harvey, Todd. 2003. “Jack Tales and their Tellers in the Archive of Folk Culture.” Folklife Center News XXV 4: 7-10

Lang, Andrew. 1889. The Blue Fairy Book. London: Longmans, Green and co.

Lang, Andrew. 1890. The Red Fairy Book. London: Longmans, Green and co.

O’Brian, Patrick. 1972. Post Captain. New York and London: W.W. Norton.

Opie, Iona and Peter. 1974. The Classic Fairy Tales. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Perdue, Charles, ed. 1987. Outwitting the Devil: Jack Tales from Wise County, Virginia. Santa Fe: Ancient City Press.

Pollack, Rachel. 2008. The Tarot of Perfection. Prague: Magic Realist Press.

Pollack, Rachel. 1996. Godmother Night. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Randolph, Vance. 1976. Pissing in the Snow and Other Ozark Folktalkes. Urbana, University of Illinois Press.

Roberts, Leonard. 1955. South from Hell-fer-Sartin: Kentucky Mountain Folktales. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press.

Steel, Flora Annie. 1918. English Fairy Tales. London and New York: MacMillan.

Tolkien, J.R.R. 2002. The Annotated Hobbit. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin/

Williamson, Duncan and Linda. 1987. The Thorn in the King’s Foot: Stories of the Scottish Travelling People. New York: Penguin.

Willingham, Bill. 2002. Fables: Legends in Exile. New York: D.C. Comics.

Discography

Hicks, Orville. 1990. Carryin’ On. Whitesburg, KY: June Appal Recordings.

Hicks, Ray. 1977. Ray Hicks Tells Four Traditional Jack Tales. Sharon, CT: Folk-Legacy Records.

Long, Maud Gentry. 1947. Jack Tales told by Mrs. Maud Long of Hot Springs, North Carolina, 1947. Edited by Duncan Emrich. Washington, DC: Library of Congress American Folklife Center

McKenna, Frank. 1990. Told In Ireland. Holywood, Northern Ireland: Ulster Folk and Transport Museum.

Various Artists. 2000. Scottish Traditional Tales. Edinburgh, Scotland: Greentrax Records.

Filmography

Fixin’ to Tell About Jack, VHS. Directed by Elizabeth Barret. Whitesburg, KY: Appalshop, 1975.

Jack the Giant Killer, DVD. Directed by Nathan Juran. 1962. Santa Monica, CA: MGM, 2004.

Jack and the Beanstalk: The Real Story, DVD. Directed by Brian Henson. Santa Monica, California: Artisan Entertainment, 2001.

Gallery with Captions

Jack Tales

From an 18th Century chapbook of “Jack and his Stepdame.” By then it was called “The Friar and the Boy,” but the boy was still named “Jack.”

From an 18th Century chapbook of “Jack and his Stepdame.” By then it was called “The Friar and the Boy,” but the boy was still named “Jack.”

From an 18th Century chapbook of “Jack and his Stepdame.” By then it was called “The Friar and the Boy,” but the boy was still named “Jack.”

Richard Chase, collector and author of the 1943 collection The Jack Tales, playing the dulcimer at the American National Folk Festival, Philadelphia, 1944. Library of Congress.

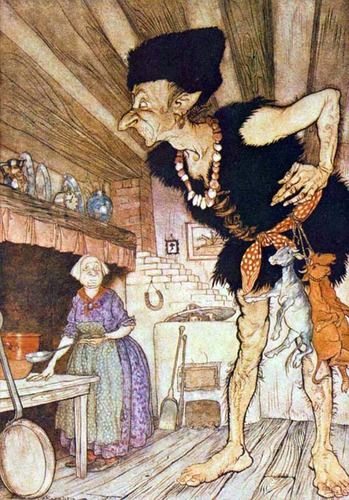

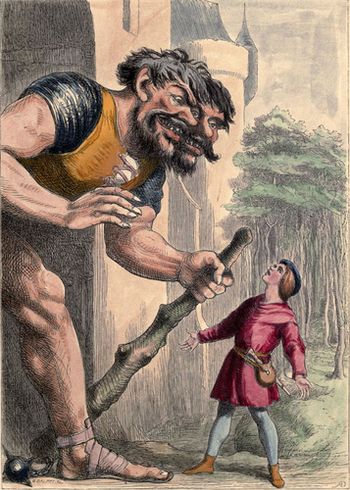

An illustration by Richard Doyle from The Story of Jack and the Giants, London: Cundall & Addey 1851.

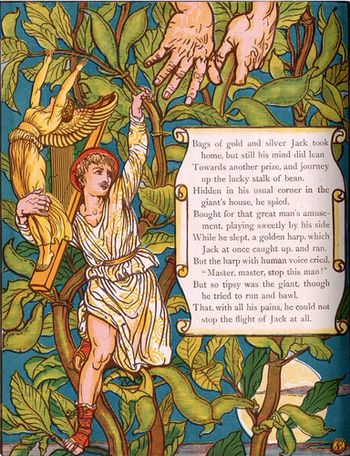

Illustration of "Jack and the Beanstalk" by Walter Crane for The Blue Beard Picture Book, London: George Routledge and Sons, 1875.